The Oscars just tanked. Beautiful small but barely-watched movies, combined with boring woke politics, produced an epic collapse in ratings.

But the significance of a work of art does not ultimately lie in its ability to reach a mass market. Now, seems as good a time as any to visit another small, beautiful film released last year about two Dutch Catholic painters. The one, Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675), is one of the greatest artists of all time. The other Henricus Antonius “Han” Van Meegeren (1889-1947) became perhaps the greatest art forger of all time.

What does it tell us about the integrity of art when the value of a painting depends on the name attached to it? This is not a new question. Another Catholic painter, Andy Warhol, played and replayed on this theme in his work. But The Last Vermeer takes exploring this question to a different level by setting up a dramatic confrontation between a Nazi hunter who cares more about truth than revenge, and an artist who ultimately chose revenge over truth.

Revenge against whom? Against the tyranny of the modern critic over the creative artist, of course. The sneers of the critics in response to Van Meegeren’s first exhibit of paintings in Amsterdam left him humiliated and his career in tatters, but with his taste for alcohol, women, and lavish living intact. His response was to unleash on the art market a series of exquisitely painted fake Vermeers along with a new finishing process that would foil the experts’ chemical tests used to authenticate the age of the painting.

Van Meegeren’s new Vermeers burst onto the international art scene; they were praised and pronounced authentic by the most distinguished critics and hung in major museums (including the National Gallery in the United States).

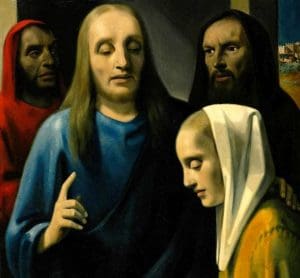

During the Nazi occupation, Van Meegeren even sold the widely lauded Christ with the Adulteress to future Nazi war criminal Hermann Goering.

After the liberation of the Netherlands, Van Meegeren was charged with collaborating with the enemy, a capital crime under Dutch laws. Van Meegeren’s spectacular defense was to declare himself an art forger who had patriotically tricked the Nazis into trading priceless looted Dutch masterpieces for fake Vermeers. To prove it, he painted a brand-new Vermeer, Jesus Among the Doctors, right in the courtroom as the two-year legal proceeding progressed (in the movie, which telescopes the action, he completes the painting while in prison awaiting trial).

It was sweet revenge for Van Meegren: the critics were publicly humiliated, and he became an instant national hero for hoodwinking the Nazis into trading genuine Dutch masterpieces for fakes.

To explore its themes of integrity, the film The Last Vermeer chooses for its protagonist not Van Meegeren himself but a Captain Joseph Piller (Claes Bang), a Jewish Resistance fighter in the Netherlands who is charged with investigating Van Meegeren for the Allied Forces. While investigating the sale of Christ with the Adulteress to Goering, Piller discovers a lascivious photo of his wife, Johana (Susannah Doyle), attending one of Van Meegeren’s debauched parties with a Nazi official. The discovery severs his marriage and separates Piller from his beloved little son. Piller has every motive for pursuing Van Meegeren: doing so would satisfy a deep desire for revenge for the desecration of his wife, his people, his country. And yet, he chooses to defend Van Meegeren in the Dutch courts. “It’s not the man, really” he explains, “it’s that he’s innocent.”

Piller’s emotional plight is tangible but nonetheless upstaged by the virtuoso performance of Guy Pearce as the suave, cultivated, and endlessly fascinating artistic genius Van Meegeren, with his elegant Amsterdam home and his extensive collection of cut-glass liquor decanters, to the point the viewer might briefly wonder why Piller’s story is in the film at all. But both performances are upstaged, at least in the courtroom scenes, by the looming presence of Van Meegeren’s fake Vermeers themselves.

The Van Meegeren trial attracted such international attention that newsreel footage of it survives to this day, and the settings of the courtroom in The Last Vermeer faithfully replicate history. Over the judges’ heads hang the enormous religious paintings hauled in for the trial: Christ With the Adulteress, a Last Supper, and The Supper at Emmaus, a 1937 painting that had persuaded Abraham Bredius, the leading Dutch expert on Vermeer, to pronounce the work “the masterpiece” of Vermeer’s career and thus help launch Van Meegeren’s lucrative business churning out similar paintings for museums and private collectors.

To a twenty-first-century eye, these paintings look nothing like the smaller genre paintings of seventeenth-century Dutch domestic life—The Milkmaid (1658) or Woman Reading a Letter (1664)—that we typically associate with Vermeer, but they are haunting.

Vermeer converted to Catholicism only on his marriage to Catharina Bolnes in 1653. The sincerity of Vermeer’s Catholic faith has been the subject of long-running debate. Of the 34 paintings now universally attributed to Vermeer only two, Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (1654-1656) and Allegory of the Catholic Faith (1670-74), have religious themes, and only the latter is overtly Catholic in subject matter, depicting an altar crucifix that would have been unthinkable in a Calvinist church of Vermeer’s youth.

But that was the nature of Vermeer’s economic and social milieu. The long, war-torn struggle of the Low Countries starting in the sixteenth century to free themselves from rule by Habsburg Spain had left the Dutch Republic an overwhelmingly Protestant country by the time Vermeer was born. Catholics, associated with Habsburg rule, were tolerated, even accepted in the social fabric, but forbidden to hold public office or worship in public. They met for Mass in warehouses and private homes, likely including that of Maria Thins, Vermeer’s wealthy mother-in-law, where the Vermeers, who never had much money, lived. Reformed doctrine forbade religious images inside churches, so there were no commissions for the huge religious paintings that were features of Counter-Reformation church decoration in the Catholic countries of the seventeenth century. Art production during the Dutch Golden Age was strictly for the private market, and market forces and fashions determined its content. While some prosperous citizens of Delft and elsewhere hung paintings with Biblical themes in their homes (which the Reformed Church allowed), most preferred smaller works with secular themes: portraits, landscapes, still-lifes, and the genre paintings at which Vermeer became a virtuoso.

But some art historians have discerned subtle Catholic imagery even in some of Vermeer’s secular paintings. The University of Montana’s Valerie Hedquist argues, for example, that the veiled, clearly pregnant young woman in his Woman Holding a Balance (1662-1665) is an image of the Virgin Mary, and that Vermeer included in the painting such traditional Marian symbols as the pearl and the mirror. In any event, Vermeer named one of his sons Ignatius after St. Ignatius Loyola, the Jesuits’ founder and another son became a priest.

Van Meegeren, by contrast, was born into a middle-class Catholic family in Deventer, in the eastern Netherlands. He seemed to have abandoned the practice of his faith early on, probably in rebellion against his father, a schoolteacher, who ridiculed and tried to stifle his son’s artistic talent. In one respect, however, he retained a Catholic sensibility: He revered and practiced traditional representational art, refusing to participate in the Expressionist and Cubist movements that critics of the early twentieth century baptized as the only serious art. Van Meegeren deemed them decadent. He won prizes and praise for meticulous draftsmanship and made a fair living traveling around Europe painting portraits. Then, in 1923, critics derided an exhibition of his paintings as derivative and lacking in psychological depth. He maintained that the trauma of that damning criticism was what drove him to forgery: He would play the critics for fools and prove his artistic genius by turning out counterfeit masterpieces that they would dub masterpieces.

Soon enough, working through layers of art dealers so as to protect his anonymity, Van Meegeren was flooding the art world with “newly discovered” paintings by the masters of the Dutch Golden Age: Franz Hals, Gerard ter Borch, Pieter de Hooch, Dirck Van Barburen, and, of course, Vermeer—all finely executed and plausibly resembling known works by those painters. He used seventeenth-century canvases from which he scraped the existing paint and mixed pigments from materials that the seventeenth-century masters had used themselves.

Wealthy collectors snapped up the paintings, and some ended up in museums. (Indeed, to this day it is unclear whether certain museum Vermeers are actually Van Meegerens—and a supposed Van Barburen owned by the Courtauld Institute in London was found to be a likely Van Meegeren as recently as 2011.) These were all smaller works, and by the early 1930s Van Meegeren was plotting to execute a Vermeer on a grander scale—The Supper at Emmaus–that would finance his expensively debauched lifestyle.

Vermeer was an ideal choice. His work fell into obscurity after his death and had few collectors. Not until the 1860s did art historians focus on his luminous genius and begin to rank him as one of the greatest of the Dutch Masters. Lost Vermeers and imagined Vermeers regularly surfaced after that, and it was not hard to believe that still more of them hung undiscovered in musty European corners. Van Meegeren spent several years perfecting a Vermeer-like brushstroke and teaching himself how to recreate the colors of Vermeer’s limited palette. He spent a small fortune on tubes of expensive genuine ultramarine, made from pulverized lapis lazuli, a semi-precious stone that makes a brilliant blue paint. Vermeer lavished ultramarine on his paintings (his famous Girl With a Pearl Earring, painted around 1665, uses ultramarine for its subject’s bright blue cap.) To achieve craquelure, the hardened, time-cracked surface of centuries-old oil paintings, Van Meegeren mixed liquid bakelite, the stuff of old telephones, into the paint.

The real measure of Van Meegeren’s brilliance as a forger, however, was his fabrication of an entirely new artistic style for Vermeer. His model was not Vermeer himself, but Caravaggio. The style of that Italian Baroque painter (1571-1610) had influenced a generation of Northern European Catholic artists, especially in Utrecht, a Dutch city that remained predominantly Catholic throughout the Reformation and whose churches continued to commission art. They created their own striking versions of Caravaggio’s large-scale religious paintings: naturalism, chiaroscuro effects, and simple, dramatic compositions in which the painted figures looked as though they had been photographed at a moment of high emotion. Art historians of the 1930s wondered whether Vermeer, too, had imitated Caravaggio, especially during his early career when he made at least one known painting with New Testament subject matter (Christ in the House of Mary and Martha looks somewhat Caravaggio-esque and very unlike Vermeer’s later work). The Supper at Emmaus, modeled on a 1610 painting by Caravaggio dealing with this post-Resurrection appearance of Jesus, responded directly to the historians’ speculation. It was the missing link.

Once Bredius enthusiastically endorsed it as a genuine Vermeer, a wealthy shipowner bought the painting for $5.5 million in today’s dollars and donated it to the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam. That opened the reputational and financial floodgates for Van Meegeren to generate and launder through his dealer network even more counterfeit Vermeers in the same style with similar New Testament themes, including the Christ With the Adulteress that he sold to Goering. Overall he earned about $50 million in today’s dollars from his ventures into art forgery.

After Van Meegeren’s conviction and death, the value of his fraudulent Vermeers collapsed. With the passage of time, they look more obviously like concoctions of the 1930s and 1940s—perhaps Van Meegeren’s version of the Expressionism he found so aesthetically deficient. It has been easy for many of today’s critics to deride Van Meegeren as a mediocre painter and the experts such as Bredius who swallowed his bait as vain, self-aggrandizing fools.

But as Friedkin’s movie The Last Vermeer suggests, the Van Meegeren affair raises genuine and complex questions about the meaning and value of art.

While watching the courtroom scenes in the film, I found myself unable to take my eyes off The Supper at Emmaus and Christ With the Adulteress. They were compelling in their stark geometric composition and their focus on the liminal and unknowable presence of Jesus as a figure who sets astonishing revelations in motion. None of those paintings was a knockoff; they were genuine originals, just not by Vermeer. What if tastes in art change again over, say, the next 70 years, and we regard the avant-garde twentieth-century art that was the reigning style when Van Meegeren painted as childish rather than cutting-edge? In a 2010 documentary Fiso Lammertse, a curator at the Van Beuningen Museum, pointed out that people loved The Supper at Emmaus during the 1930s. “They thought it was beautiful. And it is beautiful. That wasn’t wrong.”

The climactic scene of the film is about the nature of integrity to one’s calling. Piller and Van Meegeren meet up after Van Meegeren is acquitted of treason and basking in his glory as a national hero. Piller confronts Van Meegeren with another truth: great artists in every age become great because they persist through the rancor of critics, through the ignorance of audiences, through public failure, in remaining true to their own artistic vision. What instead did Van Meegeren do with all his talent? The art forger has no answer.

In The Last Vermeer Captain Piller discovers—and this is true to history—that Van Meegeren had, during wartime, sent an autographed copy of a book of his drawings to Hitler with a fawning dedication. In the end of the movie, Piller throws the book into the trash and goes to reconcile with his wife. She is flawed like Van Meegeren, flawed like himself. She is the woman taken in adultery, to whom Jesus said in John’s Gospel, “Neither will I condemn thee. Go, and now sin no more.”

It could be said that at least in this fictional story Van Meegeren did not paint his fake Vermeers in vain.

Charlotte Allen is a culture and arts reporter for Catholic Arts Today