Editor’s Note: This is one of a series that might be called “Forgotten Catholics”: Great artists, novelists, and poets who are not known as Catholics. In this essay you will meet one of the great 20th-century Latin American sculptors, a refugee from Communist Cuba, who in times of crisis turned to St. Ignatius’ examen exercise to ground himself in the presence of God. Surely a re-valuation of this man’s work in light of his faith is long overdue.

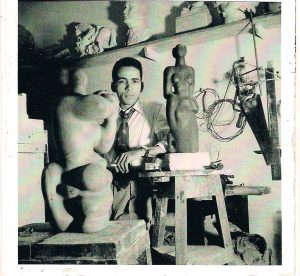

Roberto Gabriel Estopiñán (1921-2015), a Cuban sculptor who emigrated to exile in the United States not long after Fidel Castro’s revolution in 1959, is considered one of Latin America’s most important 20th-century artists.

His work, which includes drawings and prints as well as sculptures in wood and bronze, is in the collections of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Detroit Institute of Art, among many locations. He is best known for his stark, disturbing renderings of political prisoners, the fruit of his own experiences as a dissident under both Castro and his predecessor, the dictator Fulgencio Batista, and for his representations of the female torso that can remind viewers of both classical statuary and the high-modern, abstractly elongated work of Henry Moore.

What is little known about Estopiñán is the centrality of his Catholic faith in both his life and his work.

He was born in Havana to a father from Asturias in northwest Spain and a mother of African descent. His father died when Roberto was seven years old; he and his younger brother were raised by their mother, a maternal uncle, and a grandmother. He attended the local public school but went to a Jesuit church near his home for catechism classes. His youthful exposure to the Jesuits would affect him for the rest of his life. In moments of political crisis he would turn to the examen, a five-step prayer technique that is part of St. Ignatius Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises and focuses on the laying out of the day’s events in the awareness of the presence of God. Besides being a means of discerning one’s relationship to God, the examen has a visual component—seeing in one’s mind how God is working in one’s life—and it informed Estopiñán’s sense of visual aesthetics and would serve as a compass in his art.

Estopiñán was something of a prodigy. At the age of fourteen, he won the first prize in drawing at the Centro Asturiano, a regional association for Cubans of Asturian descent. Shortly afterward he received special permission to enter the San Alejandro Academy of Fine Arts in Havana, which usually did not accept minors. At the school he was mentored first by its director, the painter Armando Menocal (1863-1941), then by the landscape artist Antonio Rodríguez Morey (1872-1967), and finally by Juan José Sicre (1898-1974), regarded as one of Cuba’s greatest sculptors. Sicre, a professor of sculpture at the Academy, had helped introduce European modernist art to Cuba, and from the 1930s through the 1950s had sculpted monumental figures in Havana of José Martí and other Cuban national heroes that stand to this day. Estopiñán was first Sicre’s student, then his assistant, and, finally, his colleague for the next fifty years.

After graduating from San Alejandro in 1942, Estopiñán began simultaneously teaching art at the Ceiba del Agua School for young men, assisting Sicre in public art projects and developing his own artistic vision. He also traveled widely, to Mexico, New York, France, and Italy. From the late 1940s through the 1950s his sculpture evolved from an early neoclassical phase under the influence of Maillol to what he defined as “formalist humanism”: emphasizing the abstract beauty of the shapes he sculpted while not abandoning the human figure as the basis of his work. As the 1950s progressed he chose to carve in native Cuban woods as well as weld scraps of various metals. Although he was obviously influenced by Henry Moore and Julio González (1876-1942), a Spanish modernist sculptor whose iron weldings prefigured Estopiñán’s weldings in bronze, he had already created his own visual language.

Estopiñán, an avid reader, was preoccupied by the tensions of the Cold War, the aftereffects of the Nazi concentration camps, and the nuclear detonations that marked that era. There seemed to have been a historical breakdown—and this affected his ideas about people’s inner lives, as well as about what representing the human figure meant for artists after such historical breakdowns. He also felt a call to civic duty, especially after Batista’s coup of March 1952 established a military dictatorship that suspended Cuba’s constitution and most civil liberties in what had been a fragile democracy. Estopiñán joined the Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil, an anticommunist, pro-democracy student-based organization that opposed the Batista regime.

During those years he read voraciously, from anti-communist writers on the left such as George Orwell, Ignazio Silone, and Arthur Koestler to Catholic philosophers such as Jacques Maritain and Étienne Gilson, as well as the poetry of Dante and Valéry.

He was deeply affected by Gilson’s 1955 Mellon lectures at the National Gallery that later became a book, Painting and Reality. Gilson argued that modern painting and sculpture did not aim to represent or imitate the natural world, but rather to add to it. For this reason, Gilson argued, modern art must be distinguished from mere “picturing”—producing images of actual or possible beings. The modern artist, according to Gilson, dismantles the unnecessarily descriptive, the overly decorative, and the merely illustrative, proposing instead an expressive language of the essential that is ultimately more spiritual than conventional depiction. Estopiñán decided to ground his aesthetic practice in Gilson’s theory of the “pure plastic elements” that characterized modern art, as well as Valéry’s definition of a classic: “a work that is measured by three standards: quantity, quality and variety.”

Throughout the 1950s Estopiñán simultaneously experimented formally with his sculpture and engaged in revolutionary acts against the Batista dictatorship. He participated in strikes, printed and delivered leaflets, and hid other revolutionaries on the run. He also began his arresting sculptures of political prisoners, winning prizes in national exhibitions. After the triumph of Castro’s revolution, the new regime rewarded his activism with diplomatic postings as a cultural attaché in Egypt, Czechoslovakia, and China. His experience in China while Mao Zedong carried out his program of forced collectivization of agriculture, suppression of Christian churches, and disastrous Great Leap Forward that resulted in tens of millions of deaths by famine, confirmed misgivings that he had already been experiencing about Cuba just a few weeks after Castro’s triumph.

“My intuition told me that instead of democracy, it was populism manipulated by a demagogue, that rule of law was not restored but replaced by the mob, and that the new regime was turning against the very Catholic church that had supported it,” Estopiñán told me an interview in 2014. “Communist China was simply the nightmare confirmed. I had seen the future and it was hell.”

Back in Cuba in early 1961, he encountered a brutally sectarian society where opposition was not tolerated. He saw only four choices for him: adapt and lose your soul; be imprisoned; be executed; or save your soul and your life by going into exile. He chose the latter.

On his way to a new diplomatic assignment in Honduras, he got off the plane in Tegulcigapa, went straight to the U.S. embassy, and requested asylum. In exile first in Miami, then in New York City, he was overcome by a profound existential crisis: How could he have been fooled? Why and how did a revolution meant to be democratic sour so quickly into totalitarianism? He tortured himself looking for an answer, but the Jesuit examen came to his rescue, as did Maritain and Camus.

He also made new discoveries among 20th-century writers who had found meaning in Christian faith: Simone Weil and Thomas Merton. A fellow Cuban exile, the Catholic poet Israel Rodríguez (1925-2008), lent him two books by contemporary Catholic theologians that trace the roots of the atheism and nihilism that undergird many modern ideologies: The Drama of Atheist Humanism by Henri de Lubac and The God Question and Modern Man by Hans Urs von Balthasar. Both were Jesuits, and both were energized by the Second Vatican Council and its efforts to revitalize the Catholic Church as a bulwark against modernity’s aggressive secularism while at the same time speaking a language that modernity would understand.

After arriving in exile in the midst of this crisis of faith and ideology, Estopiñán slowly started to draw and sculpt again. But he found his earlier formalism hollow and lacking. He began to study the Romanesque sculpture of twelfth-century Western Europe, in which the elongated stone figures of Christ and other biblical personages dramatized religious meaning, as well as the work of the German Expressionist sculptor Ernst Barlach (1870-1938), whose realistic but stylized woodcarvings and bronzes that recalled the sculptures of saints on the façades of Gothic cathedrals displayed intense spiritual yearnings. Estopiñán needed to return to the human figure in a less abstract manner, more directly, more emotionally, in the best tradition of religious art.

And he did.

Throughout the 1960s the human figure returned to Estopiñán’s art, often in specifically religious images. During this decade drawings and sculptures of crucifixes, crucifixions and Calvaries appeared by the dozens, together with his continuing representations of political prisoners along with warriors and exiles. Ranging from minimalistic simplicity to dramatic expressionism, these works communicate depth of feeling and religious intensity. Estopiñán viewed his challenge as translating his inner life, his faith, into these works. I believe he succeeded; those works are grounded in profound Christian belief.

Years later Estopiñán recalled: “I wanted to be true to myself, which meant being a modern artist and a believer. [Georges] Rouault and Barlach could do it, as well as abstractionists like [Alfred] Manessier and [Jean René] Bazaine. But so could artists who were not traditional believers, like Matisse in the chapel at Vence, like Germaine Richier’s crucifix in the church at Assy. I am not talking of grotesqueries like Le Corbusier’s church [an asymmetric concrete chapel with tiny windows erected in 1955 in Ronchamp, France], but something deep and clear and balanced.”

During the 1970s Estopiñán’s style shifted toward a more organic figuration, reflecting his desire to convey a synthesis between the human body and plant life. By the 1980s he had arrived at a new classicism, austere and simplified, in which the female torso whose renderings he became famous for and the political prisoners who continued to haunt him were his most constant themes, right through the end of his life.

In 2002 Estopiñán and his wife, Carmina Benguría, a performance artist and fellow exile, moved from New York to Miami. There he produced two etchings with crucifixion themes, carved a study for what he called a “resurrection crucifix,” which he hoped to make life-size for a chapel, and made drawings for a sculpture of a Madonna and Child (now in the collection of the chapel at Xavier University in New Orleans) that he was not able to execute.

Shortly before his death at age 93 I interviewed him for the last time. I asked, “Tell me in one sentence what your work is about.” He responded, “It’s about opening up matter–stone, wood, metal–and allowing the Spirit to dwell. In the end, I am merely a tool of God.”

Roberto Estopiñán pursued an authentic modern art that was also reflective of his intense Catholic faith. Hans Urs von Balthasar had raised “the God question and modern man” as an expression of the difficulty of maintaining Christian belief in a radically secularized and nihilistic age. Estopiñán provided an answer.