[Editor’s Note: It is with great pride that we announce that the Benedict XVI Institute and Wiseblood books are bringing the English translation of Sono Ayoko’s novel of St. Maximilian Kolbe “Miracles” back into print this August. The novel may be purchased at WisebloodBooks.com]

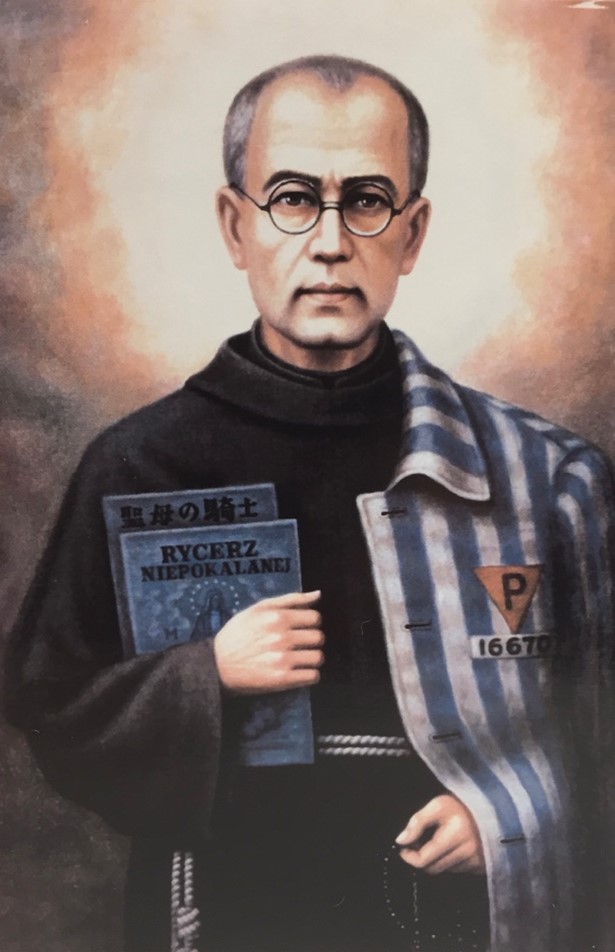

St. Maximilian Kolbe, O.F.M. Conv., “the saint of Auschwitz,” is best known as a European saint. He was a Polish friar who was taken prisoner by the Nazis during World War II and died in Auschwitz after volunteering to take the place of Sergeant Franciszek Gajowniczek, one of ten men condemned to die in the starvation bunker as punishment for a presumed escapee. He was canonized in 1982 by his fellow Pole, Pope St. John Paul II, who declared him “a martyr of charity.” To many, Kolbe represents light in the darkness of World War II, hope in the despair of the Holocaust.

That’s Kolbe in a nutshell. Or so it would seem. What this well-known story leaves out is a major part of his life and his ministry: the story of St. Maximilian Kolbe in Japan. This tale includes the tremendous cultural impact he had on the Japanese imagination and the impact Japan had on him during the early 1930s.

Father Maximilian Kolbe lived and worked in Japan for six years. The only surviving “Gardens of the Immaculata” (missions founded by Father Maximilian Kolbe) are in Poland and Japan.

Fr. Kolbe was quite proud of his (limited) ability in the Japanese language. He would include Japanese phrases in his letters (taihen yorokonde imashita= it brings me great joy[i], and even kodomo no tame ni yoroshiku, atarashii shimpu sama no tame ni mo= greetings to all the children and to the new priests).[ii] And he had the friars study Japanese at Mugenzai no Sono (the Garden of the Immaculata) in Nagasaki. He used a Japanese language textbook by Arthur Rose-Innes, a Protestant who was living in Japan at the time. Kolbe wrote to him, urging him to convert to Catholicism. Rose-Innes, in his reply, gave Kolbe a copy of the Japanese textbook he had written. Conversational Japanese was not enough. He even learned to write some characters and included them in his Nagasaki Diary (which was mostly written in Polish).

Why did Kolbe decide to go to Japan in the first place? During the 1920s there was a renaissance in missionary work among Catholics. Fr. Alfonso Orlini, the Father General of the Conventual Franciscans, had sent out a letter to his friars encouraging them to expand their foreign missionary work. The Conventual Franciscans had opened a mission in China in 1925 and another in Zambia in 1929. It would have been logical for Kolbe to simply apply to one of those missions. But Providence—or as Kolbe would say, “the Immaculata”—intervened.

In Europe, Kolbe had met four Japanese students on a train. He conversed with them, and they impressed on him the urgent need for missionaries in Japan where there were so few Christians. Kolbe thanked them and gave them each a Miraculous Medal. The encounter left a deep impression on Kolbe, and he made up his mind to go to Japan—with no knowledge of the country, its culture, history, or language! It was an audacious move.

When Kolbe approached Fr. Orlini in 1930 for permission to start a mission in Japan, he met resistance. Not surprisingly, he was told to go to China instead. But Kolbe, with characteristic determination grounded in his firm belief that Japan was the plan of the Immaculata, was not deterred. And on March 7 1930 he boarded a ship in Marseilles with four other friars headed for Japan. They stopped briefly in Shanghai (out of respect for Fr. Orlini). Kolbe left two friars there to explore the situation and he continued on to Nagasaki with the remaining two. The friars left in Shanghai soon after joined them in Nagasaki. Immediately on landing, Kolbe went to the landmark Ōura Cathedral to meet with Bishop Hayasaka. Ōura Cathedral (“The Church of the 26 Martyrs”) was the site where the Hidden Catholics were discovered on March 17 1865 and remains Japan’s oldest and most beloved Catholic church.

Just over a year after his arrival in Japan, Kolbe was pouring the foundation for the second Garden of the Immaculata, the first outside of Poland. He named it Mugenzai no Sono, a literal translation of “Garden of the Immaculata.” Later, the name was changed to Seibo no Kishi (“Knights of the Blessed Mother”), when they found out that mugenzai was a homonym for “endless sin”. It is still known as Seibo no Kishi today, as is the still-extant Catholic press and journal that Kolbe founded.

There is a pious legend that Mugenzai no Sono was protected from the atomic bomb because of Our Lady’s guidance in selecting the original site, located behind some hills. The much older wooden Ōura Cathedral (built in 1864), where Maximilian and his friars had begun their work in Japan, also survived the atomic bombing, even though it was more exposed to the effects of the bomb. Ōura Cathedral and Mugenzai no Sono were over three miles from ground zero, and damage from the bomb was generally limited to two miles from the epicenter. Certainly, the hilly topography helped protect Mugenzai no Sono, but so did the distance.

From April 24 1930 to May 23 1936, Kolbe was based at the Mugenzai no Sono friary in Nagasaki. During that period, he left for two months in 1930 to attend a Provincial Chapter in Poland, as well as a three-week excursion to India in 1932 in a failed effort to establish a Garden of the Immaculata there, and a six month trip back to Poland for his order’s chapter in 1933.

In spring 1932, Fr. Kolbe realized a long-held dream. Before he left Europe for Japan, he visited Lourdes and prayed that he would be permitted to build a Lourdes grotto in Japan. The location immediately behind the friary was ideal for a grotto: a quiet place with a rocky cave and even spring water. The grotto was completed and a statue of Our Lady of Lourdes was placed there on May 1 1932, an appropriate way to start the Marian month.

The best evidence of Maximilian Kolbe’s love for the Japanese people, their culture, and their language comes from a letter he sent to Ms. Clara Izaki in Nagasaki after he had returned to Poland. He wrote, “I will never forget Japan; indeed, I always pray for it. I will work with every effort for the salvation of Japanese souls. The Japanese are a people who really search for the authentic religion, so they will obtain many graces from the Lord God.”[iii] The letter was written entirely in Japanese.

But even after he left Japan, Father Maximilian Kolbe’s influence on the Japanese imagination continued, largely through the little-known (in America) Japanese wave of literary conversions. (See my previous Catholic Today essay “Beyond Endo: The Hidden Renaissance of Japanese Catholic Novelists”).

The noted Catholic novelist Shūsaku Endō modeled the character Mouse in his 1963 short story “Fuda-no-Tsuji” in part on Fr. Kolbe. Like many of Endō’s short stories, it flits between the present and the past: both Tokyo of the 1930s and of the Edo period when thousands of Catholics were martyred in Japan (“Fuda-no-Tsuji” is the site of the 1623 martyrdom of 50 European and Japanese Catholics). The protagonist Inoue knew Mouse as a German monk (Kolbe’s surname was German) who worked at his university, but he clearly had little respect for the weakling. Decades later, at a reunion with his classmates, he finds out that Mouse had been put in a concentration camp where he offered himself in place of a condemned prisoner and was starved to death. Endo’s Inoue reflects: “and if, in fact, Mouse had died for a friend—for love—then that was not a tale from the long-gone days of the Edo period, but an incident that commanded a place in the man’s own heart.”[iv]

Strangely enough, it was Rolf Hochhuth’s controversial play The Deputy (translated into Japanese in 1964) that led to an explicit interest in Kolbe by Japanese. The Catholic novelist Ayako Sono has confessed that it was Hochhuth’s play that sparked her interest in Kolbe and she eventually traveled to Poland to research her classic novel Miracles (1973) that describes in a very personal way her reflections on the saint, as she followed his footsteps from his childhood home in Pabianice to Krakow where Kolbe studied in the seminary, to Kolbe’s great monastery-city of Niepokalanow and ultimately to Auschwitz.

One can learn a great deal about Kolbe’s life in Europe from Sono’s novel. But as a writer of fiction, Sono is not primarily concerned with history, geography, or even theology. Her work cuts deeply below the surface of temporal phenomena to reveal the heart and soul of Kolbe—and indeed of Christianity itself. The true miracle of Kolbe, she tells her readers, is his fulfillment of the Lord’s commandment “to love one another as I have loved you.”

Sono draws boldly from the Marxist philosopher Vítêzslav Gardavsky’s God is Not Yet Dead to explain how Kolbe could offer his life in place of Franciszek Gajowniczek: “Miracles are performed. They are the nodal points in the web of history, the junctures where something unique takes place, an incident which can never be repeated. And if we look at it this way, love turns out to be the radically subjective element of history.”

Miracles is not a novel for the feint-hearted. Sono makes it clear that the love she is pursuing is not a sentimental emotion, a mere feeling, or something that simply comforts one. She anticipates her readers’ expectations and often challenges them. Perhaps the most infamous instance is when the narrator (is it Sono herself?) confesses that she doesn’t believe in eternal life. In another novel Sono wrote just a few years later, she quoted no less than St. Thérèse of Lisieux saying “I no longer believe in eternal life.” Sono’s point—a subtle, perhaps too dangerously subtle, one—is that faith in Christ only for one’s own self-interest is a poor excuse for faith. Rather, she calls her readers to imitate Maximilian Kolbe—even Christ himself—and put love ahead of life. It is a stiff challenge, perhaps one too hard for many mortals.

Sono’s 1973 novel Miracles may have inspired her friend Endō to take up the topic of Kolbe more explicitly than he had done in his earlier short story. Endō himself credits his 1976 visit to Auschwitz. He was in Poland to accept a prize for the Polish translation of his novel Silence. The very next year, Endo wrote two short non-fiction pieces about his experience there for the Japanese media: “In Poland” and “Seeing the Auschwitz Concentration Camp” (neither has been translated into English). His short story, “Japanese in Warsaw” (1979) deals with Kolbe in a powerful, allusive manner and deserves to be more widely read. It is included in the anthology Five by Endo (New Directions, 2000).

“Japanese in Warsaw” outlined the conceptual and structural approach Endō would take in his historical novel Sachiko (1982): both works see Kolbe as the link between people of different cultures and races, and both works discuss Kolbe’s life in Nagasaki.

In Sachiko, Endo describes Kolbe in Nagasaki in the early 1930s, and although it is historical fiction (not accurate in all historical details) it does enrich one’s understanding of what life in Nagasaki was like for Kolbe. Sachiko, a Catholic girl living in Nagasaki, is the symbolic link between Kolbe, whom she met as a young girl, and Shūhei, a young Catholic man with whom she fell in love. Most of the novel is centered on World War II—Kolbe has left Japan and word reaches Nagasaki that he has died, while Shūhei is drafted into the kamikaze “suicide” air corps. The novel, in essence, is Sachiko’s memories of the troubled and complex place that Catholic Nagasaki was during the 1930s and early 1940s. Widely available, the novel deserves a careful reading by anyone interested in Maximilian Kolbe, Japan, or the universal Catholic faith.

Endō’s Sachiko is less historically accurate than Sono’s Miracles; but Sono’s work doesn’t give as much attention to Kolbe’s years in Nagasaki. Fortunately, there is a forthcoming work that for the first time gives an accurate, in-depth account of Kolbe’s life in Nagasaki. Tōmei Ozaki, O.F.M. Conv.’s Father Kolbe in Nagasaki has just been translated into English by Professor Shinichiro Araki and will be published this August by The Academy of the Immaculate.

The work is based on Friar Ozaki’s personal interviews with many of the friars of Seibo no Kishi who knew Kolbe, as well as his own painstaking research. The book is replete with many rare photos of Kolbe and his circle, as well as inside information from the friars who lived in Nagasaki with Kolbe. It was originally published in Japanese in 1982, a momentous year for those interested in Kolbe. That was the year Friar Zeno, Kolbe’s close companion in Japan, was called to Heaven. It was also the year St. Maximilian Kolbe was canonized.

Friar Ozaki is a fascinating source for information on Maximilian Kolbe. As a boy, he and his mother used to visit Mugenzai no Sono regularly (after Kolbe had left in 1936). At one point, he wanted to join the friars but he faced opposition from his relatives who wanted him to look after his widowed mother. He narrowly escaped death on August 9, 1945, but the atomic bomb took his mother. After wandering alone in the atomic wasteland for several days, he found himself at the front door of Mugenzai on Sono. They took him in, and he never left. Friar Ozaki knew many of the friars who were close to Maximilian Kolbe during his years in Nagasaki and their testimonies enrich his work.

St. Maximilian Kolbe’s feast day this August 14th promises to be a watershed date. With Friar Ozaki’s book available in English, along with English translations of Ayako Sono and Shūsaku Endō’s novels on Kolbe, we are finally able to know more about those years Maximilian Kolbe spent in Japan and the lasting impact they had on him. Thanks to these books, more and more people can come to know St. Maximilian Kolbe, not as a European saint, but as a saint of the universal Catholic Church.

A Brief Interview with Professor Shinichiro Araki of Nagasaki Junshin (Immaculate Heart) Catholic University (July 12, 2021) on the Impact of St. Maximilian Kolbe in Japan

Professor Araki, how would you describe the position of St. Maximilian Kolbe in Japanese culture today? Do many Japanese, Christian or not, know anything about him? What do they know? And what do they think of him?

“The percentage of Catholics among Japan’s total population is only 0.4 percent. Taking this into consideration, we may say that St. Maximilian Kolbe is exceptionally well known and loved in Japan. His popularity depends largely on Ayako Sono and Shūsaku Endō’s novels, as you suggested in your article. One more contributing factor to his fame is that St. Kolbe is sometimes dealt with in Japan’s school education. One typical example is that one of Endō’s essays about St. Kolbe’s sacrifice in Auschwitz is taken up in one of the most popular Japanese textbooks used in the high schools. Many Japanese students are impressed by St. Kolbe who sacrificed his life for a stranger.

Friar Ozaki, the author of Father Kolbe in Nagasaki passed away on April 15, 2021. The previous year, NHK, the only public broadcaster in Japan, produced a TV program which dealt with Friar Ozaki’s atomic bombing experience in Nagasaki and his encounter with Father Kolbe’s sacrifice. This program was aired nationwide twice last year and once again in Nagasaki just after Friar Ozaki passed away. Through this program even more Japanese came to know Father Kolbe in relation to Nagasaki.

This year, August 9 is the 76th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. People in Japan will recall Friar Ozaki who was one of the most famous “hibakusha” (atomic bomb victims) in Nagasaki, and his beloved St. Maximilian Kolbe on this memorable day.”

Kevin M. Doak is the Nippon Foundation Endowed Chair in Japanese Studies at Georgetown University. Among his publications is Xavier’s Legacies: Catholicism in Modern Japanese Culture (UBC Press, 2011).

[i] Kolbe letter from Niepokalanow to Mirochna in Nagasaki, Nov. 11, 1936; cited in Claude Foster, Mary’s Knight: The Mission and Martyrdom of Saint Maksymilian Maria Kolbe (Marytown Press 2013), p. 497.

[ii] Kolbe letter from Niepokalanow to Mirochna in Nagasaki, June 16, 1939; cited in Foster, p. 546.

[iii] Kolbe letter from Niepokalanow to Clara Izaki in Nagasaki, September 12, 1936; cited is Foster, p. 1249.

[iv] Shūsaku Endō, “Fuda-no-tsuji,” in Stained Glass Elegies, trans. Van C. Gessel (New York: New Directions, 1990), p. 68.