Editors’ note: This is the first of a three-part profile of Frank La Rocca, a composer who lives in the Bay Area. La Rocca also did the interview for Catholic Arts Today with the greatest living Catholic composer of classical sacred music: Sir James MacMillan. Frank’s music can be heard at FrankLaRocca.com.

“Late have I loved you, O Beauty ever ancient, ever new, late have I loved you!” St. Augustine.

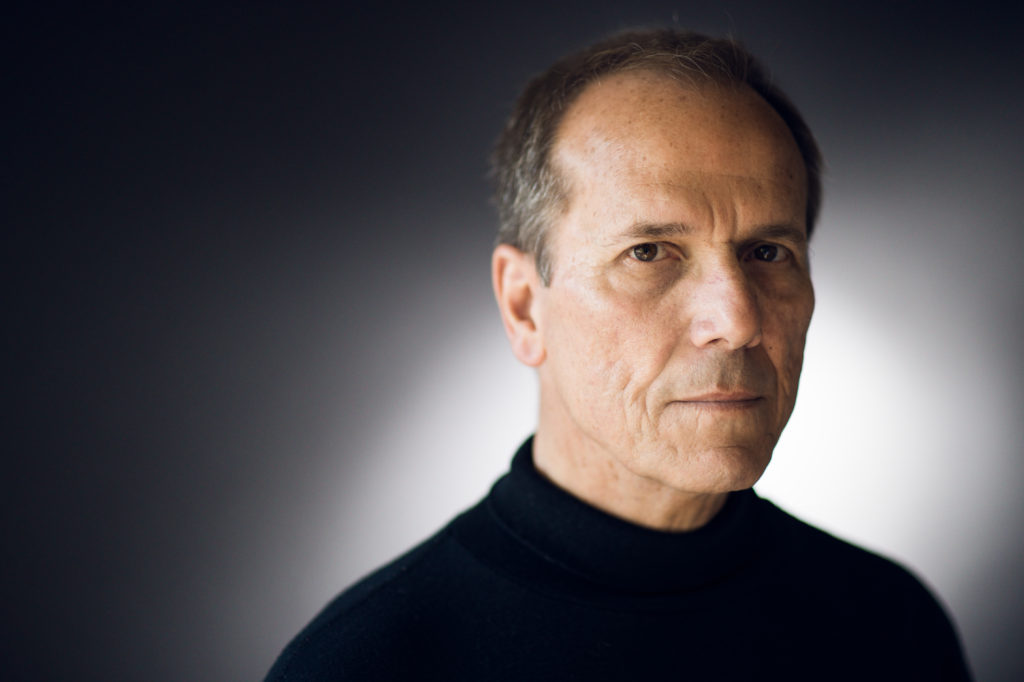

Frank La Rocca is a Bay Area composer whose work has received widespread attention.

On December 8, A new Marian Mass of the Americas composed by La Rocca will be sung at St. Mary’s Cathedral. The Mass bring us closer to both Our Lady of Guadalupe and Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception by weaving North and South and Latin Americas’ sacred music traditions into one composition. This extraordinary event is made possible by the generosity of Benedict XVI Institute for Sacred Music and Divine Worship’s donors: Come, mark your calendars.

How good is Frank La Rocca’s music? Expedition Audio placed La Rocca among the contemporary sacred music immortals: “Mr. La Rocca joins the company of, among others, Gorecki, Pärt, Schnittke, and Tavener in combining the music of ancient times with current compositional techniques…in his own unique and effective way.” Fanfare wrote: “The California-based composer, for over 30 years professor of music at California State University, East Bay, writes music unmistakably inspired by liturgical chant and the masters of the Renaissance and Baroque but filtered through a musical sensibility informed by the works of 20th-century modernists: beauty ever ancient, ever new very literally. The American Record Guide dubbed La Rocca’s work “a wholly original artistic synthesis.”

But R.J. Stove in Catholic World Report put his finger on the really striking thing about Frank La Rocca: his moderate fame relative to his immense achievement. “Perhaps the most pernicious single delusion to have afflicted musical thought over the last two centuries is,” he writes, “The Myth of Artistic Inevitability. The central teaching of this myth can be summarized in the slogan, ‘You can’t keep a good man down.’” Stove says people under the influence of this Myth then erroneously assume, “if a particular musician of stature fails to find a mass public, it is fundamentally his own fault.”

Could this help explain why Catholic art patrons, once common, are now so relatively rare? One little-recognized reason is that our culture now has two metrics for excellence: the opinion of experts and success in the mass market. The classic role of the patron falls between these two postmodern stools: “The arts evolve,” one potential patron told me when I made the case for Catholic Arts Today, which is in part our case that to thrive, artists need a community and so does the audience who loves the arts.

But the market for culture, like other markets, requires people who act in it in various roles: So the tech industry tends to cluster in communities where the talented can grow their ideas before the market has shown they will succeed. Other creatives require similar incubators, and (I argue) especially Catholic creatives, lest we lose artists to punditry or marketing. Genius cannot be summoned into being, but the conditions of craftsmanship can be, as the Renaissance should teach us, those tiny city-states that produced such lasting masterpieces of art.

The conditions under which great art can be created and find an audience are clearly not culturally inevitable. Across time and space, experience teaches us they are rather the exception than the rule. One of the fundamental conditions, I submit, and one of the inspirations for Catholic Arts Today is that there are a relatively small number of people with access to financial or cultural resources who pay attention.

Stove goes on: “The main reason the myth is absurd is that it utterly fails to take totalitarian cultures, or even ordinary modern Western leveling, into account. Suppose that there had emerged in the twentieth century a composer who combined the gifts of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven in his own person. Those gifts, far from guaranteeing him popular acclaim and a berth in Grove’s, would not have done him a blind bit of good if he had been stuck amid the Holodomor, or amid Khmer Rouge Cambodia, or amid Maoist China’s Cultural Revolution, or (if he had possessed Jewish ancestors) amid Nazi-occupied Poland. Indeed, his exceptional abilities would have increased the likelihood of his being hunted down like a rat.”

This is just a preliminary aside to the wonder Stove experienced relatively late in life of discovering the music Frank La Rocca makes: “All this serves as a prelude to noting several facts: first, that there flourishes in America a composer named Frank La Rocca; second, that his creative talent for religious music is remarkable; third, that one can have been a professional musician—indeed a professional church musician—for decades without having encountered his name, let alone his output; and fourth, that those in that ignoramus category had included myself, until his CD In this Place, was recently brought to my attention.”

Then the accolades from Stove fly: “uncommonly interesting”; “traces of Arvo Pärt” yet “conspicuously not by Pärt himself”; “a composer comfortable not only with the setting of Latin words but with large musical structures, a fact that in itself separated him from most of the minimalists”; “an atmosphere of mystical devotion, Messiaen being occasionally implied in the piled up vocal harmonies and the suggestion that ‘the still point of the turning world’ had been intuitively (rather than logically) arrived at. But it could not be classified as fake-Messiaen either.”

“It is among the most difficult of all pedagogical tasks to depict, through mere words, musical originality,” Stove concludes, “This musical originality la Rocca has somehow acquired, without the smallest detectable straining after it.”

The straining that leads to great art happens behind the scenes.

On a breezy San Francisco day last December, I sat down for four hours with Frank La Rocca to uncover the mystery of the man and his musical journey. It is the journey of a man who takes music and faith seriously; a man for whom music is not ornamentation or entertainment, but a language that expresses what only a soul can experience.

One of the reasons that Frank La Rocca is not yet a household name is this: In obedience to his soul’s yearnings, La Rocca has switched classical music genres three times, losing the audiences and the accolades he had won to pursue the music that his soul commanded him to make. Sometimes the clichés are true.

A Catholic Schoolboy Joins the Sixties

Frank La Rocca did not exactly turn on, tune in, and drop out during the Sixties. But he shared two great generational experiences of the Sixties: the immigrant assimilation into the American elites as Ivy Leagues de-Waspified, and the rebellion of Catholic schoolboys in the face of the sexual revolution’s siren call.

In person, at age 66, Frank is handsome, distinguished, preppy even. But when he talks he waves his hands frequently and expressively, like the son of Sicily he is. His father was first generation Sicilian. His mother was first generation Ukrainian.

He began as a Jersey boy, in the shadow of Manhattan’s looming, alluring towers.

“I was born and raised in Clifton, New Jersey; I could see the New York skyline from the backyard. The city where I grew up was ethnic immigrant families Italian, Irish, Poles and Jews. I never met a Protestant until I was 10 years old,” Frank laughed.

That’s when the nuns told Frank’s parents he needed a more intellectually challenging school. So his folks eventually sent him to Montclair Academy, a prep school for the Ivies. “Sturdily Protestant,” Frank recalls it, “We sang ‘A Mighty Fortress is Our God’, ‘Onward Christian soldiers’ and other stirring Protestant hymnody.”

Frank’s first spiritual crisis occurred on Nov. 22, 1963, at age 12. At the Montclair Academy’s athletic awards ceremony Frank saw the school secretary come out and pull the Headmaster to a side corridor. The Headmaster quickly strode back to the podium, interrupting the speaker and made the terrible announcement: “The President has been assassinated.”

Like most Catholics of his generation, Frank idolized Pres. John F. Kennedy. “I even recited the Gettysburg address in his Boston accent, because I thought that made me sound presidential,” he told me.

On the long bus ride back to Clifton after the early dismissal, Frank felt the world had ended. “I was as devastated and confused as anyone could feel. On the way home, I had a serious conversation with God—angry, confused, indignant—this was the first time I ever conceived of feeling that way about God,” he told me.

The following February, just a few months later, the Beatles hit the Ed Sullivan show. Frank La Rocca joined the Sixties. “The gloom of the assassination was being dispelled, everyone was happy. That was the trigger for me to pursue a music career more vigorously. I left the Church when I stopped going to confession and I stopped going to confession when I started making out with my girlfriends,” he said wryly.

He is not the first Catholic man of a certain age to tell me that story.

His first professional musical gig was a high school band called “The Establishment,” which got paid to play high school dances and local parties. “Because I played the organ, they thought I would be cool,” Frank remembered, “There was just fantastic camaraderie among the 6 of us in the band.“

Over 40 years later those bonds of friendship played a peculiar role in bringing Frank La Rocca back to his childhood Catholic faith. But that was much, much later.

Senior year, Frank La Rocca applied to Harvard and Yale, because that is what the big fish (class president, coolest band, prettiest girlfriend) at Montclair Academy did. Yale accepted him. His parents wanted him to be a lawyer. By his junior year, he knew he wanted to compose music instead.

After graduation, he was accepted into Berkeley’s graduate program in music composition, mostly on the strength of his Yale professor’s recommendation. California here Frank came, breaking another apron string tying him to his immigrant past.

Academic Modernism Stamps His Soul

Berkeley, in the ideological heyday of 12-tone zealotry, tried very hard to put its stamp on Frank La Rocca’s soul, not without partial success and at great cost to his musical vocation.

“I had to study with teachers whose musical styles could not be further from mine. They were very, very stern academic modernists, writing the most fractured forbidding unattractive music,” Frank recalled, “That was the goal to be pursued: Fractured, Forbidding inaccessible to all but the most academic ears.”

To survive, Frank told me, “I found a composer they could tolerate but I genuinely liked: Bartok. For my teachers, it was basically Schoenberg or nobody. Bartok was a little too accessible, too visceral. But Bartok was at least within the pale of Berkeley’s academic ideology.”

Some of his teachers disliked him. He was humiliated in front of other students for his failure to be sufficiently stern, fractured and forbidding. Yet he learned: “I learned to compose from talking to my fellow students, seeking out those who like me rebelled against the Berkeley establishment. We all secretly despised the fractured modernism. Some had more courage than other to go against the grain in their own work, but we all felt like fellow travelers banded together to find room to breathe and grow. We had our own little Alt-seminar. In which we taught each other things and commented on each other’s work. We lived in the catacombs.”

But towards the end of his Berkeley years, locked in male agonistic conflict, Frank La Rocca decided to prove his teachers were wrong. “Towards the very end of my time at Berkeley, I decided that before I went I wanted to prove to my teachers that, had I been by nature attracted to the kind of music they were promoting, I would have been able to do a good job. I’m going to play their game. I am going to write a piece of 12 tone music. I’m going to make this the most sophisticated and forbidding and inaccessible thing that I can conceive. Well, I wasn’t able to achieve that entirely, but the piece did sound like what one of them might have written in a more conservative mood. Very spiky, dissonant, aggressive. I showed it to my teachers, and their jaws dropped. They said. ‘Really. This is very good stuff. Wow.’”

Frank La Rocca was a good enough 12-tone composer that, when Andrew Porter, then the New Yorker’s famous music critic, listened to a string trio by La Rocca at a Berkeley concert, he was impressed. “I got my first review in The New Yorker in which Porter praised the ‘elegant craftsmanship’ of Frank La Rocca’s string trio,” Frank smiled.

Living well is the best revenge. After graduation Frank got the job he loved that paid the bills for 30 years, teaching at Cal State-Hayward.

But as a composer, he struggled with the internal contradictions between his aspirations and his Berkeley modernist straitjacket.

End of Part 1

Scroll down and click on the video to experience one of Frank La Rocca’s sacred compositions: O Magnum Mysterium. Hear more at FrankLaRocca.com. And don’t forget to mark you calendars for the December 8 Marian Mass of the Americas at San Francisco’s St. Mary’s Cathedral. It will be worth a trip.