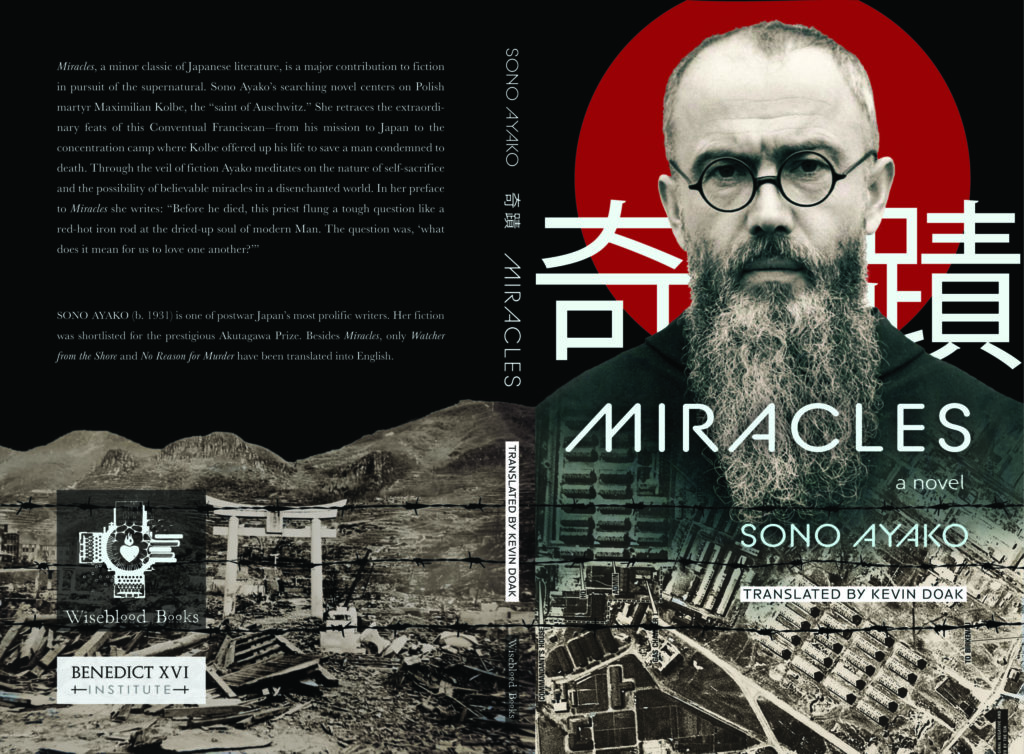

Editors Note: We are proud to publish an excerpt from this English translation of the Japanese novel Miracles, by the Catholic convert Sono Ayako who is considered one of Japan’s finest living novelists. Miracles was recently brought back into print through a collaboration between Wiseblood Books and the Benedict XVI Institute. The novel, which tells the story of a lukewarm Catholic Japanese woman who travels to Europe to learn more about St. Maximilian Kolbe, and finds her faith transformed, may be purchased here: https://www.wisebloodbooks.com/store/p114/miracles-sono-ayako.html

Auschwitz

The entrance to Auschwitz was packed with people and automobiles. Nothing around suggested the dark atmosphere of intrigue; rather, it all seemed like the entrance to a zoo or a museum. How can people come here with such a carefree attitude as if the “death” of other human beings was a mere spectacle? Just as I was thinking that I would never come to this place if I didn’t have to, I was pushed through the gates by the crowd.

We went into one of the most typical of the barracks. The walls were lined with photographs of the people who had been interned there. They said that, except for the Jews, prisoners who came here from the winter of 1940 to about 1943 all had their photographs taken. When one thinks of those people who didn’t even have a photo taken of them, could we say that these were better off because at least there was some evidence that they had existed? Most of them stared right at us as we walked past them, with their eyes bulging from their sockets, wearing their prisoner uniforms that looked like striped pajamas. You could see the fear in their deep-set eyes and swollen Adam’s apples. I couldn’t shake the impression that they were just like the eyes of fish about to die. As I was thinking these were the eyes of despair, the expressionless eyes of dying fish, I suddenly decided to walk down the middle of the hallway.

I then realized they were anything but expressionless. It was as though they were silently calling out to me.

“Wait a minute!” one of them said to me.

“Listen to me. Hear what happened to each and every one of us!”

The dead in the photographs knew I had come to write about Father Kolbe—or so it seemed to me. But they also seemed to know that a writer should write about the many unknown people rather than those who are already famous in history. But in the end, Brother B told me he had found Father Kolbe’s picture, and once again I was standing before the face of this dead priest.

Block 14 where Father Kolbe was assigned was closed to the public, so Brother B took us to Block 11 where the starvation bunker is. It was the very last block of buildings that were all in a neat row and, while the building itself wasn’t any different from the others, in between it and the block next to it was a sight that struck one right in the heart. The space was about the size of a tennis court, and people were milling about, unable to leave even as the cold evening air was already descending on us. Facing us was a wall of bricks piled up to the height of about the second story of the buildings. In front of it were two rows of thick railway ties set on end, six in each row, black as if they had been painted with tar. Here and there, gold and silver papers were stuck on them. There were flowers placed at the base of the black wooden wall, and the candles that were lit along the ground flickered like will-o’-the-wisp.

This was where death sentences by firing squad were carried out. The blood of 200,000 people seeped into the ground under that wall. Were those tinfoil stars stuck on the black boards to mark the spot where victims stood until they fell with the report of the guns?

In one of the opened windows to the underground room there was a bouquet of red carnations. That’s how we knew that it was under that window that Father Kolbe met his end.

“They consider Father’s death to be a martyr’s death, so people keep bringing red flowers as offerings,” Father O explained to me.

There was something about the events that led to Father Kolbe meeting his end in this room that was deeply suggestive of the stories in the New Testament.

Father Kolbe’s final journey, so similar to the Way of the Cross, began on May 29, 1941. On the evening of that day, Father Maximilian Kolbe and three hundred and twenty companions were disgorged from a freight car that had arrived at Oświęcim. The Friar Ladislaus Swies who arrived at Oświęcim with Father Kolbe tells us:

“While we were riding in that freight train from Pawiak to Oświęcim, someone starting singing hymns and Polish songs. Lots of people joined in the singing. I wanted to know who had started it, and I saw it was Father Kolbe. Since I like to sing and joined in singing in harmony with Father Kolbe, he took an interest in me.

“The mood was a heavy one. But nonetheless, thanks to Father’s Kolbe’s songs and words of encouragement, after a bit we recovered our good cheer.”

Father’s new name was prisoner number 16670, and his house was penal servitude Block 17.

Already Father’s own passion was being prepared for him at a place of which he was completely unaware. On April 23, about a month before Father had arrived at Auschwitz, a prisoner had escaped from Block 2 and the camp commandant Höss had come up with a new method of punishment—to seal up ten prisoners in the underground bunker of Block 11. They would be given no water or food until the escapee returned.

Just as when on Calvary Christ gave everything he had to the criminals crucified next to him down to his final moment, so too did Father Maximilian Kolbe become a source of strength for the souls of those imprisoned with him. Mieczysław Kościelniak tells us that Father Kolbe would talk of how the great and all-powerful God gave Man the trial of suffering to prepare him for a better life, and he encouraged them all to endure this suffering as it would all end soon enough.

Once, Dr. Joseph Stemler was told to take corpses to the crematorium. He found himself face to face with the dead bodies of two prisoners. They were completely naked, and the expressions on their faces showed they have suffered torture. Joseph Stemler was a war veteran, but when he looked at those horrible dead bodies, he simply froze up.

“Come on, let’s move them.”

Stemler picked up one of the blood-smeared corpses and put it in a box and then carried it over to the crematorium. Then, once again he heard the voice behind him.

“Holy Mary, pray for us.”

Stemler felt as though the words poured strength back into his body. He had to wait by the foul-smelling crematorium until the bodies were burned. Finally, their job finished, they started to leave and again he heard the voice behind him.

“Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord.”

That was when Stemler first knew it was Father Kolbe. Father had a history of tuberculosis and wasn’t able to maintain even a minimum standard of health in the concentration camp. His fever wouldn’t come down, so he was sent to the quarantined Block of the Invalids for suspected typhus patients. In the three weeks he was in the Block of the Invalids, Father Kolbe heard confessions from the other patients and offered prayers and blessings for the dying.

Dr. Stemler, who was in the Block of the Invalids with him, testified that Father Kolbe firmly believed that good always triumphed in the end.

“Suffering does not have the power to produce anything. Only love has the power to produce everything. Suffering cannot conquer us but will only help make us stronger. So that those who come after us will find happiness.”

Father Kolbe firmly grasped Stemler’s hand to press his point. But while Stemler was overwhelmed by these words, he remained unconvinced, as his heart was still full of anger.

Someone escaped. It was July 31. The guard dogs returned from the swamps looking dejected. The prisoners had already been standing at attention for over three hours. Gino Lubich writes that they no longer looked human, but seemed like grotesque dolls. But they were not dolls. They were shackled with fear, for they knew only too well what would happen after a prisoner escaped.

After 9:00 in the evening they finally heard the order to dismiss. Prisoners brought out a large pot of soup, but they were not allowed to take any. It was only to allow the aroma of the soup to cut right through their stomachs. Then, the pot of soup was taken to the edge of the ground and poured out right in front of them.

The prisoners of Block 14 were allowed to go to bed, but not one of them was able to sleep. They suffered from hunger and anxiety. If one person escapes, ten will die. Would it be me?

The next morning, the prisoners were called to assemble. The escapee had not been found. The prisoners who had not had sufficient food for several months and now had had nothing at all to eat for the last twenty-four hours were once again forced to stand at attention.

“One hour seemed like a century. The sun roasted their heads like chestnuts. Their throats had dried up from lack of nourishment, and their muscles were wrenched from terrible cramping.” One after another, the prisoners began to pass out. The S.S. would kick them with their field boots. And if that didn’t bring them back to consciousness, they were dragged over to a corner of the grounds and left there. After a few hours, those bodies formed a mountain. At 6:00 pm, the prisoners who had been out on work detail returned. Fritzsch approached the prisoners from Block 14 who were still standing in rows.

“The escapee has not been found. So, ten of you will die in the starvation bunker. Understand? After that, it will be twenty of you.”

He began walking in front of these people who had broken out in a cold sweat.

“His calm pace seemed like a funeral march. Fritzsch was a very dramatic person. I have no doubt that while he walked like the angel of death among these living corpses, his ears were tuned to the magnificent power of Wagner’s works.”

He would suddenly stop and, in what was likely very poor Polish, order them:

“Open your mouth and show us your teeth! Stick out your tongue!”

Wasn’t that more like how one judges the quality of a horse than how one treats a human being? After this oral cavity inspection, he would suddenly point to his left and cry out:

“This one!”

Thus, one by one, the victims were chosen.

“Farewell! Next time we’ll meet in heaven. Long live Poland!”

Among such cries, one could make out a whimpering voice. “How cruel. Farewell to my wife, and to my children.”

It was the voice of Sergeant Franciszek Gajownicek. He held his head in his hands and was crying.

Suddenly, a man walked confidently up to the Commandant. His soft voice carried over the men like a soft breeze.

“Who is that? What does he think he’s doing? Is he crazy?”

Someone said it was Father Kolbe.

“Polish pig. What do you want?” Fritzsch demanded.

“I’d like to take the place of one of these men.”

It seemed as if a spell had come over everyone there. They were too startled to move.

“In whose place do you want to die?”

“For this one. He has a wife and children.”

He said it as only a priest who has renounced marriage for life could.

“Who the hell are you?”

“A Catholic priest.”

“Accepted.”

The S.S. officer at his side erased 5659, which was Gajownicek’s prisoner number and instead wrote Father Kolbe’s number, 16670. The ten men selected were ordered to strip. Now all they had on was tattered underwear. And then they walked toward Block 11—of course, in their bare feet. Father turned his head a bit to the left and recited a prayer.

“At that precise moment, beyond the high voltage electrified barbed wire fence, the sun was giving off its last rays. And then the huge, burning disc sank into the distant marshlands and was seen no more. The sky turned the color of the blood of the martyrs.

“That evening I saw the most beautiful sunset in my life.”

So said an Auschwitz survivor about a setting sun he recalled in late July 1941.

The starvation bunker was pitch black. There, the prisoners had their remaining possessions taken from them. When the S.S. officers left, they spit out the lines, “You’re gonna wilt away like tulips.” From then on, everyday one could hear the sound of voices in prayer coming from the starvation bunker. Bruno Borgowiec, who served as interpreter and waste disposer, said, “every time I went down there, I felt as if I was going into the basement of a church. I’d never seen anything like it.” Of course, what he found was not just people completely saved by the power of prayer. Every time Borgowiec opened the door and went into the bunker to remove human waste, some of the prisoners would cling to him like madmen, begging for water. When anyone showed enough physical strength to put up some resistance, the guards would kick him in the stomach until he was laid out flat on the concrete floor. If that didn’t finish him off, they’d settle it with a single gunshot. Borgowiec thought it was an easy job since he didn’t have much waste to remove. The reason was that the prisoners who were suffering from thirst would drink up everything in the lavatory buckets. Like the ebbing of the tide, one by one the people would die off. And with every day, the voices singing and praying would become fewer and fewer.

“Every time we looked in on them, others would be lying on the floor, but Father Kolbe would be standing or kneeling with a serene expression on his face, and he would greet us. Even the other guards respected Father Kolbe, as they knew how he came to be in here. I heard one of them say the following, ‘I’m telling you, this priest is a real man. You don’t see many like him.’”

It was on August 14 when the phone call came to the clinic and Dr. Boch took it. He just stood there petrified with the color gone from his face, listening. In the end, he merely replied,

“Jawohl” (certainly).

He put down the receiver and entered the room with the glass door cabinet. He prepared four intravenous injections. After attaching sterilized needles, he took a large beaker with phenol written on it and filled the four syringes with it. Taking the syringes with him, he then went to the underground starvation bunker. Some days earlier, the other six survivors had fallen silent. Borgowiec secretly observed all this in the shadows. And he knew that they had to hurry up and empty the bunker as other condemned prisoners were waiting. The doctor entered the starvation bunker in his white coat and after a second or two Borgowiec heard him say,

“This will end it all.”

When the doctor had left the room, Borgowiec saw the priest motionless, leaning against the wall with his eyes wide open and a clear expression on is face, as if he were still alive.

Standing outside the starvation bunker, I thought to myself that maybe Father Kolbe had conducted a certain experiment without ever having intended to. He proved that humans somehow can survive for fourteen full days without a drop of water. During that period, cruel temptations must have occurred to him. He had no water or food. At some point during those fourteen days, they must have carried out executions by firing squad just outside the gloomy underground bunker. How Father Kolbe must have envied those whose sufferings were ended quickly by a bullet.

Pushed along by the wave of people, I exited the building. I felt completely numb to the bottom of my heart and merely followed wherever Friar B led me. When I regained my senses, I noticed a small plaza. I was told it was where Rudolf Höss, the designer and commandant of Auschwitz, was hung. Right behind it there was a crematorium positioned as if it were half-hidden. I followed the crowd down the steps. When I stood in this space that was like a huge, underground cavern, I found I no longer had even the strength to feel afraid—this in spite of the fact that with my phobia, the gas room was what I had greatly dreaded. I simply stood there in the middle of that room. What I was afraid of was touching that wall that so many people, deceived into believing that they would be showering and then locked into the room, gassed with Zyklon B, and just before they died of asphyxiation, clawed at in their last moments of anguish.

But much to my surprise when I saw the two ovens next door, I felt relieved. This came from my recognition that by the time they were brought here, those people had already been released from their sufferings. I had already made up my mind not to feel sad over such things as how Father Kolbe’s ashes were scattered all over the place. But when I saw the flowers placed in front of an open cauldron that looked kind of like a strongbox, I said to myself, yes—this is actually a happy place . . .

At that moment, I was sure of only one thing. I didn’t want to say another word. I realized that something deep within me, something I had long cherished and believed in, had been smashed to pieces. Could it be true that everything I had believed about mankind until now was all an illusion?

Crestfallen, I left the crematorium. I saw a light in the distance, but around me all was night.

[Translated by Prof. Kevin Doak]