In a recent essay Joseph Bottum pins the novel’s decline less on screens and social media than on metaphysical flatness. Much contemporary fiction either inhabits a character at close range or—in a more recent trend—zooms out to offer 30,000-foot omniscience. But at its best the art of fiction is both subjective and objective, getting into the characters’ heads and hearts while detaching us enough to confer a superior understanding. To achieve this depth, however, requires both a sense of the distortions of our age and a clear vision of the good life.

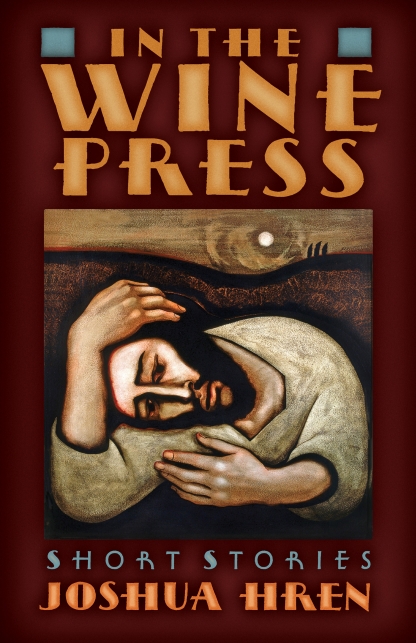

Few writers have either; fewer still possess both. Joshua Hren (editor of Wiseblood Books which is about to publish my novel Minor Indignities) is one of those who both sees clearly and is equipped to interpret what he sees. His new collection takes us to the heart of dysfunctions—familial, clerical, intellectual—that plague our world while offering a revivifying sanity.

“Horseradish,” the opening story, is just shy of twenty pages. It presents a nighttime conversation between a father and his son on the rickety porch they built together. They’ve gone out to watch a comet, but as they stand physically “closer than they had been in years” they have the sort of serious, awkward exchange that most of us in the same position would do our best to flee. The son goes on the attack, forcing his dad to confront past abdications, but while their oversharing dredges up memories, some fond (the father grew up in what he recalls with pride as the “Slovenian ghetto”), others troubling, what eventually emerges is a more recent trauma: the son is there because he decamped after losing his temper with his wife and hurling a salt shaker through a window.

With this revelation, the see-saw tilts. The father takes control, admonishing and firm, but also paternally tender:

“I maybe never gave you enough. Affection,” he said.

“Dad, “ I said. “Oče.”

“Don’t,” he commanded me, cuffing my wrist with his hand. “Listen. Maybe I never did. But listen. I don’t want to hear how you never touched your wife like that. How you never laid your hands on her. I’m not interested too much in what you didn’t do. But I’ve been wondering one thing for a long time. Do you ever? Touch her. Why am I going to die without ever having held a grandchild? Are you two…”

My arms stuck out like a poorly-clad scarecrow, and I swear I saw him look up, a terse search of the sky, as though he hoped a bird would blind me with dung for failing to give him descendants.

There may be nothing so tricky to represent without mawkishness as the fall of barriers between two people so close as to make intimacy unbearable. By story’s end Hren has given us reconciliation without sentimentality, and symbols—the porch as unstable artifact of the father-son bond, the once-in-a-lifetime comet mirroring a brief window for genuine connection—that work on every level.

Another story, “Old Blood,” reaches toward reconciliation with similar tact: a school shooter’s almost-but-not-quite-girlfriend phones her Vietnam vet uncle in a nursing home to invite him to move in with her. She is spurred to this act of charity by loneliness, yes, but above all by reflecting on what could have driven her former online paramour to such evil. If in his previous collection Hren trod ground more familiar to partisans of Catholic fiction—the spiritual physics of self-mortification—here he telegraphs his intentions less, and shows more restraint. The action of grace is there, but not so much in the parting of the sea within the story’s frame as in the reader’s awareness that blocked exits in the here-and-now point to liberations that fiction most successfully represents discreetly, or even a contrario.

In “Work of Human Hands,” a widow seeks healing for her twelve-year-old son, Rudy, sexually abused by their parish priest, whose predations are described with excruciating but muted realism. We are then privy to Rudy’s encounter with the virtuous but decrepit Father Sun, a wheelchair-bound traditionalist (he has Mosebach’s Heresy of Formlessness by his bedside) who nods off in mid-conversation before snapping awake again to lay hands on the boy in a very different sense, adding another layer to the story’s title:

Balancing his body with his good arm, Father searched the bureau somewhat frantically until, nodding, he heaved out an old black book whose edges were light red like the priest’s face. Father Sun’s eyes flitted fiercely across the pages. His shoulders scrunched up and his neck shot out as he searched. Peering into a prayer at the very end, he nodded again and mouthed the words, ignoring the absence of sound, and in the naked room his rasps came out loud. He pressed his hands against the boy’s head, rubbing in the water he had sprinkled there, holding his hands against Rudy’s temples until the trembling in his hands ceased, then until the boy stopped shaking.

Finally, we eavesdrop on the offending priest’s own fantasies of doing penance through bloody, self-inflicted violence—followed by his realization that a first, faint stirring of justice could be achieved only by expressing contrition directly to his victims. The story’s use of multiple viewpoints offers a sense of orchestration and design.

There is maturity in the idea running through In the Wine Press that unspectacular words and gestures contain still greater spiritual power than needed but secondary acts of physical penance. The collection’s title suggests that providence will in the course of our everyday lives devise mortifications more effective than any we invent for ourselves. And it is under the pressure they place on us that drops of precious mercy are squeezed out of our otherwise hardened hearts.

Two of Hren’s stories—“Some Other Exit” and “Their Fire is Not Quenched”—feature adolescents in rebellion. One rages against a world of spreadsheets, self-help mantras, and pyramid schemes, doctoring his Harvard t-shirt to read “Hatred” and fronting a rock band called CORIOLANUS; the other dreams of cold political mastery and a plum job with a Washington think tank but lives with his parents, whose piety he despises. Other stories address the cover-up of clerical misdeeds, the innocence tarnished by pornography, and the damage casually inflicted by political ambition. Such are the subjects—at once weighty and ticklish—Hren has taken on. We’d rather look away, but his ethic as a writer is to cut through discomfort and depression with brutal honesty. As St. Thomas knew, contemplating the truth is among the best remedies for sadness.

Set in a corner store, the collection’s last story, “Proof of the Immortality of the Soul, with Reference to Beeswax Soap,” is a high-degree-of-difficulty piece that blurs the lines between prose and poetry:

Look a broomstick-thin man with two packs of cigars bulging out of his chest, pockets fatter than his frame, man he’s chewing on his sleeves, stepping up to the clerk who’ll be here until close, squinting under the beams that illumine the things that his ma clicked her tongue at as he flicked up his finger. But he still can’t quite shake that sharp tsk when he sees unclad ladies on the covers of shellacked magazines and the color-code condoms claiming pleasures and ease and he clings, cleaves condemned, to the counter’s cliff-edge like a cold-blood-caught criminal on apocalypse eve, feeling heat if you will like a fried nervous chicken with five bona fide furies biting after his heels.

As the scene shifts to a smelly church bathroom, physical grime is likened to the buildup of sin on the soul, and you feel genuinely elated when “you” (the story is told in the second person) ends up joining a confession line. As for Hren’s method of delivering impressions in a relentless staccato, with plentiful alliteration—is it over the top? Yes. Does it work? Yes, at least for this story.

Most of the book, however, relies on more familiar narrative techniques and requires only as much investment from the reader as the author can pay back, with interest, in the currency of storytelling pleasure. This, I think, is the route forward for Catholic writers: mastery of craft united with a vision informed by faith, but never the latter without the former—and the former above all.

The Czech writer Josef Skvorecky once said that all great novels are thesis novels—and they all have the same thesis. As liberalism’s success breeds its own failure, we need works that lead our society to reexamine its basic anthropological premises, reminding us that we are wired not for radical autonomy but for communion and transcendence. Of course, such works make their point not through abstract statements but by artfully selecting details, characters, actions. Any attempt at paraphrase falls short—their intellectual meaning is accessible only by experiencing them in their entirety. While some recent novels published by mainstream houses meet this description (Christopher Beha’s Index of Self-Destructive Acts comes to mind), in the end we may have to rebuild our literary culture from the ground up.

It is with fiction like Joshua Hren’s that we can undertake this essential task.

Trevor Cribben Merrill’s reviews and essays have appeared in The University Bookman, Dappled Things, and The American Conservative, among others.