He is buried in Calvary Cemetery in Woodside, Queens under a cross and his own words: “Peace O My Rebel Heart”.

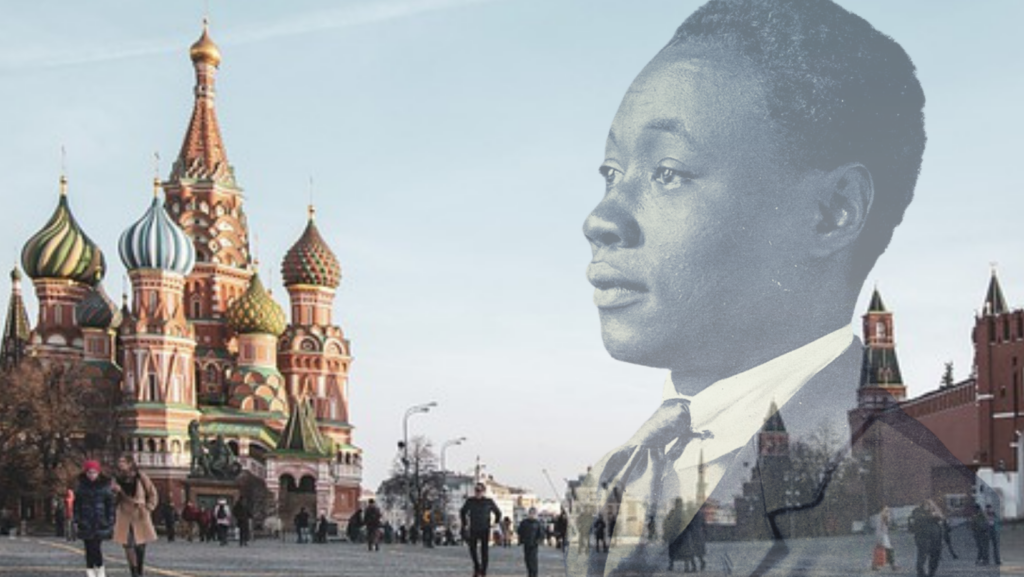

Claude McKay (1889-1948) was the first great poet of the Harlem Renaissance: an immigrant from Jamaica, a socialist tempted by Communism, an angry young man, and by the end of his life, a Catholic.

His aptly named book of poems, Harlem Shadows (1922), included work of great rhetorical power that gives voice to a defiant black consciousness, as in McKay’s two best-known sonnets, “America” and “If We Must Die”; but the most distinguished writings in this volume are short realist sketches in lyric form, at once disillusioned and earnestly sentimental, of African American life in New York City.

The actor Charlie Chaplin, then at the height of his fame as the Little Tramp, in which guise he sympathetically portrayed the poor, working man caught in the great, unfeeling machine of the industrial age, recognized a kindred spirit in McKay’s poems.

At their best, McKay’s sonnets look on urban life with sympathy and love, a quality that the poet Hart Crane would, in those years, dub “Chaplinesque.”

McKay would complement these brief vivid depictions of Harlem life with three novels—Home to Harlem (1928), Banjo (1929), and Banana Bottom (1933)—whose reveling in the seamier elements of African American life earned the criticism of the prominent African American intellectual W.E.B. DuBois.

And yet, McKay remains best known for his poems, whose faithfulness to the English poetic tradition, from Shakespeare and the Renaissance sonneteers to the Romantics, has made them hard to account for in an age such as ours, where literary scholars seem capable of appreciating only those authors whose radical politics find expression in equally avant-garde artistic experimentation.

From the Tropics to New York

McKay was born into a prosperous farming family in Jamaica. His abilities were early recognized by his family and attracted patrons; he came to brief fame as the Jamaican equivalent of Robert Burns, publishing two volumes of ballads in Jamaican dialect, in 1912: Songs of Jamaica and Constab Ballads. His family sent him to the United States to study scientific farming, first at the Tuskegee Institute, and, later, at Kansas State University. He left both institutions without a degree and moved to New York City. There, for several years, he worked in dining cars for the railroad, discovered the lively, crowded, squalid streets of urban life, and began to publish poems in Max Eastman’s socialist magazine, The Liberator.

An early sonnet, “Invocation,” suggests McKay’s aspirations as a writer. He wished to uncover the “Ancestral Spirit” of Africa that had been hidden from black Americans by “the white God.” Against this God, McKay prays,

Such lines may sound at first less complex than they really are. McKay seems to identify American whites with the Christian God and to vow to recover a black “music” and culture that has been robbed from him and his people. Other poems of the period seem to second this ambition. “The Dominant White,” for example, warns white America that God had given it many great powers and achievements in “trust,” but, because these have been abused, “God shall humble you down to the dust.”

But McKay’s seemingly strident and simple politics was always shot through with complexity. The “ancient music” McKay embraces is, first of all, the English poetic tradition as a whole. He particularly favored the sonnet, that most widely practiced modern lyric form first invented in the Italian thirteenth century, brought to maturity with Petrarch in the fourteenth, and soon spread as a literary fashion to all the modern languages of Europe. For McKay, the effort to revive “the Ethiopian’s Art” in “modern” New York entailed not a project of black separatism, but one that could give classical expression to the way of life of what was then called the “New Negro.” He wished to pour the new way of life he had discovered in the modern American city into the traditional forms of English poetry, so that African America could take its place within both the broader American culture and the deeper and older English literary tradition. He desired to join and enrich a tradition with black experience rather than to pit one against the other.

Harlem Shadows does just this. In “America,” McKay expresses his ambivalence about his adopted country. America’s racism feeds him “bread of bitterness” and “sinks into my throat her tiger’s tooth,” he begins. And yet, he cannot help but “love this cultured hell.” The “vigor” of city life, America’s sweeping “bigness” all fascinate him. And so, he assumes the position of a “rebel” within the walls of a king’s court, staring “into the days ahead.”

William J. Maxwell, the editor of McKay’s poems, observed how deeply this sonnet draws on the English tradition. America is akin to a conventional lady of the sonnets, whose beauty attracts the poet, but whose cold demeanor refuses him her favor.

The dense layering of tropes (bread of bitterness, tiger’s tooth, “tides” in the blood, a rebel at court) bears comparison with McKay’s contemporary Allen Tate, whose sonnet “The Subway” also expresses ambivalence about the modern city. In Tate’s case, it is the technological speed and grandeur of New York which fascinating and overwhelms, for McKay the anguish of the sonnet comes from his admiring a land in which he finds himself not entirely welcome.

McKay had become active in leftist black and socialist causes during the time he wrote this sonnet and yet, oddly, its conclusion does not suggest that political action will resolve his feelings about America. Rather, McKay merges his poem with P.B. Shelley’s famous sonnet, “Ozymandias,” to conclude on an image of America sinking beneath the sands of history:

Beneath the touch of Time’s unerring hand,

Like priceless treasures sinking in the sand.

This is a strange resolution indeed. McKay sees the future not as the place where justice shall triumph, but where everything he loves and hates will meet with the same fate.

In the years ahead, McKay’s politics would become ever more radical. He would visit the Soviet Union, where he was celebrated as a black American ally of the cause of international communism. Poems from every period of his life suggest his anguish and advocacy of a new political order that would allow African Americans and the poor in general to achieve greater equality and prosperity. His leftist activities did not go unnoticed by the FBI; for more than a decade, McKay was forbidden reentry into the United States.

The Ginger-Root of Benediction

In the years before his death, however, McKay shocked his friends by converting to Roman Catholicism (1944) and began contributing poems to Dorothy Day’s Catholic Worker newspaper.

Some readers have speculated that the leftist McKay was simply drawn to Day’s variety of religious socialism; they propose that his spiritual conversion was but one more political gesture. But this is not convincing. Those closing lines of “America” suggest McKay’s poetry possessed a greater horizon than the political from the very beginning. Although the political aims of much of his poetry are unmistakable, one always senses a striving after a vision that sees beyond the politics of the hour and into eternity. His imagination was as much one of celebration and contemplation as it was of righteous indignation.

This is obvious enough just from the ambivalence of his poems, where he celebrates the qualities of African American life even as he also condemns the racism that cripples it. “Alfonso, Dressing to Wait at Table” is a classic of such poems. McKay envisions a dining car waiter, singing popular jazz songs while he dresses. His voice is an image of “fine falsetto” freedom, of “carefree men,” but all this will have to fall silent when the white faces of the customers appear for dinner and decorum and segregation become one:

Soon we shall be beset by clamouring

Of hungry and importunate palefaces.

Similarly, “The Harlem Dancer” recognizes the sordidness and harshness of the Harlem demi-monde, even as McKay cannot help but admire the hard exterior and interior spiritual freedom that results for the prostitutes and others who live within it.

McKay’s poetry also always had a religious dimension. The poems we quoted above make the language of “God” sound like a merely political term, but that is not the whole story. McKay’s early masterpiece, “The Tropics in New York” captures the ambivalence that runs through many of his best poems. The poet stares in the shopwindows of New York to see the “Bananas ripe and green, the ginger-root, / Cocoa in pods and alligator pears” he recognizes from his Jamaican youth. These items from a tropical paradise, appearing before him now, bring him to tears of nostalgia: “I turned aside and bowed my head and wept.”

What is he weeping for? At least in part, the homeland of his birth he senses as also a spiritual homeland, whose “dewy dawns, and mystical blue skies” he remembers as a “benediction over nun-like hills.” The Jamaica he has left behind for the modern city of New York is not simply a land of mellow fruitfulness, or a lost pastoral akin to the “Innis Free” for which the poet W.B. Yeats had yearned, in a similar poem, two decades earlier. McKay longs for a land where the simple goodness of everyday life is an emblem not merely of physical plenitude but of religious blessing. The beauty of the island is draped in a vision of holiness.

When McKay visited the Soviet Union, he sought to celebrate the energy and achievement of the Workers’ Paradise. Oddly, he did so by writing a sonnet in praise of a Russian Orthodox Cathedral:

Bow down my soul in worship very low

And in the holy silences be lost.

Bow down before the marble man of woe,

Bow down before the singing angel host.

What jewelled glory fills my spirit’s eye!

What golden grandeur moves the depths of me!

The soaring arches lift me up on high

Taking my breath with their rare symmetry.

Bow down my soul and let the wondrous light

Of Beauty bathe thee from her lofty throne

Bow down before the wonder of man’s might.

Bow down in worship, human and alone;

Bow lowly down before the sacred sight

Of man’s divinity alive in stone.

McKay’s language betrays him into sublimity. “Bow down before the wonder of man’s might” may have originally been intended to celebrate the power and ingenuity of the modern worker, but the sonnet tugs us in another direction. It draws that line toward the “marble man of woe,” the incarnation of the Incarnate God, Christ, in an altarpiece. Man’s “divinity” is “alive in stone” not in the sense of man’s capacity to make things, but in the more obvious sense that all who enter the church and “Bow down” will see Christ himself manifest in the stonework of the cathedral. The allusion to the English romantic William Blake found in the phrase “rare symmetry” insists that this imaginative vision is primarily a spiritual one. Christ is not replaced by the ideal man of the communist future; to the contrary, all the architecture of man leads the eye beyond worldly concerns to the final beauty of Christ’s crucifixion.

Equality in the Word

Other McKay poems indicate that his break with Stalin and the Soviet Union came early—in the 1920s—and that the reason for the break was the official atheism of the Soviet State. It seems that, when McKay warned white America that God would humble it for abusing its many fine qualities, the admonishment was literal and sincere. McKay at once looked back to his Jamaican childhood as a nostalgic, elusive vision of Christian paradise, but he also looked to God to lead all persons through the fascinations of everyday life and the righteousness of political causes toward a vision that reconciles these things in the eternal God of Jesus Christ. How soon McKay himself came to understand this we do not know, but the truth that he did so long before his baptism in the Catholic Church shines through his verses. The lines are crowded with Christian references that one may be tempted to regard as mere poetic expressions until one sees how frequently they bear the thematic weight of his poems.

In the short time left to him as an active poet after his conversion, McKay spoke more directly the essentially religious language his poetry had always contained. Like all Catholics of the period, he recognized the modern ideologies of fascism and communism as “pagan isms.” He celebrates the Magi, one of whom was a “black” wise man “of the East,” thus indicating that an “Ethiopian in Jerusalem” was converted to Christianity “Long before Rome its pagan fetters burst.” He celebrates the Middle Ages as one where “Mohammedan and Christian and Jew” engaged in philosophical and theological debate, an indication that different races really can engage one another fruitfully on the plane of the intellect. Similarly, “The whites admit the Negroes have religion” is a demand for political equality in light of our equality of baptism. McKay goes further: Christianity so saturates “Negro life” that it shocks those whites who restrict their devotion to “a special place for God / On Sunday.” Black Americans are thus exemplary of the integration of piety with everyday life.

Among McKay’s late poems, however, are sonnets of pure celebration of the gift of faith, in virtue of which McKay can “face my God alone”; for the truth found “in Thy Holy Church”; for the Benedictine monastic life found at Saint Meinrad’s, in southern Indiana:

And humbly sit them at their elders’ feet,

To hear the story of Christ’s wonderous grace,

And learn God’s wisdom in this blest retreat.

Such praise culminates in his hymns of praise for “The Word” who is God. “The Word” was the last poem McKay completed, and in its lines he draws together the words that had allowed him to celebrate and look back on the “green fields” of Jamaica and the words that allowed him to give expression to the bustling life of the New York streets. But these uses of words are intended at last to “lift / Men up to know” Christ as the Word Itself “made flesh.” His nostalgic poems of recollection thus served always, and especially at the end of his life, to recall us to our origin the creative, eternal Word of God.

McKay is not the kind of poet likely to get a hearing in an age like ours. His variousness and complexity inconvenience almost everyone. At his most politically radical, he still loved the country that discriminated against him and his race. Anxious like many figures of the Harlem Renaissance to give voice to distinctively black experience, he did so in the language, and with the versecraft, of a tradition that was under assault by the novelty-craving experiments of literary modernism. Blunt in his political expression, he nonetheless took aesthetic pleasure in the shadows of Harlem and was content to live among them. Restless to see justice and a workers’ paradise on earth, he nonetheless saw from the beginning that there was a paradise beyond the radical dreams of communism to which all persons were called. He saw that there was a final truth that we do not use to advance our cause but in whose peace we are called to rest.

For this reason, McKay may be best remembered as the first great poet of the Harlem renaissance, but he should also be known as one of the first great poets of American Catholicism.

James Matthew Wilson is the Poet-in-Residence of the Benedict XVI Institute. His most recent book is The Strangeness of the Good (Angelico, 2020). His website is JamesMatthewWilson.com