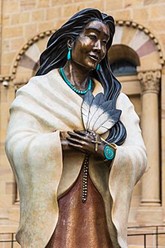

St. Kateri Tekakwitha “the Lily of the Mohawks” was born in the village of Ossernenon in present-day New York State, to Mohawk Chief Kenneronkwa and a woman raided from the Algonquin people. Before her mother was taken captive and adopted into the Mohawk tribe, French Catholic missionaries near Montreal had baptized and educated her, converting her to the Church.

At the frail age of four years, Tekakwitha lost her parents and younger brother to a smallpox outbreak that spared her life, but terribly scarred her skin and impaired her eyesight. She followed in the moccasin steps of her mother and on Easter Sunday, April 18, 1676 at the age of 19, Tekakwitha assumed the baptismal name, “Catherine,” in honor of St. Catherine of Siena. She disavowed marriage, instead vowing perpetual virginity, and eventually moved to the Jesuit mission village of Kahnake. According to Father Pierre Cholonec, Tekakwitha said:

“I have deliberated enough. For a long time, my decision on what I will do has been made. I have consecrated myself entirely to Jesus, son of Mary, I have chosen Him for husband, and He alone will take me for wife.”

The Jesuits characterized Kateri as reserved, averse to social gatherings and given to blanketing her scarred face. She slept on thorns, offering her suffering up for her family’s conversion, a Christian practice that for her recalled the traditional Iroquois ritual of drawing blood. She wanted to found a convent with a devout fellow convert, Anastasia (a friend of Tekawitha’s late mother) but the Jesuits told her she was “too young in faith.”

Hagiographers attested that on her death at age 24, witnesses watched her scars vanish, to leave her skin resplendently beautiful. As early as 1684, her gravesite had become a place for pilgrimages.

In 1885, American Catholics initiated the process for Kateri Tekakwitha’s canonization, followed by Canadian Catholics. As described on Wikipedia: “On January 3, 1943, Pope Pius XII declared her venerable. She was beatified as Catherine Tekakwitha on June 22, 1980, by Pope John Paul II.”

In his canonization homily, Pope Benedict XVI honored St. Kateri:

“There she worked, faithful to the traditions of her people, although renouncing their religious convictions until her death at the age of twenty-four. Leading a simple life, Kateri remained faithful to her love for Jesus, to prayer and to daily Mass. Her greatest wish was to know and to do what pleased God. She lived a life radiant with faith and purity.

Kateri impresses us by the action of grace in her life in spite of the absence of external help and by the courage of her vocation, so unusual in her culture. In her, faith and culture enrich each other! May her example help us to live where we are, loving Jesus without denying who we are. Saint Kateri, Protectress of Canada and the first Native American saint, we entrust to you the renewal of the faith in the first nations and in all of North America! May God bless the First Nations!”

This first American Indian saint resonates powerfully, for me and for many other Indigenous people, “loving Jesus without denying who we are.”

Walk the galleries of the Prairie Edge & Sioux Trading Post on the Dakota plains, and you will see some extraordinary works by the late John B. Giuliani, priest and painter, such as his Crow Trinity, his Cheyenne Virgin and Child and Sundancer Christ. Beneath the liberal, loquacious light from those floor-to-ceiling windows, the perfectly-mixed American Indian red ochre, corn-yellow, and gold maize of his icons flow in complete harmony and complement to the authentic Indigenous art surrounding them. There at that leisurely outland in Rapid City, the good Father stands beside Jim Little Wounded and Kevin Fast Horse, holding his own with no fear, beside Joanne Bird and Del Iron Cloud with confidence, despite Giuliani’s Byzantine style.

Perhaps against all odds, the predominant religion today among American Indians is Christianity, and in fact, given the intense and unrelenting spirituality which has always been characteristic of the culture, evidence of Christ is often the first one will encounter – as when entering, for instance, the Qualla Boundary, the Cherokee reservation inhabited by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina, where the most noticeable, immediately-recognizable structure is a church. Therefore, it should go without saying that our contemporary art scene must accept this reality, and then reflect its truth. As arts journalist, Grace Glueck, wrote in The New York Times, “Although Western art was raised on religion, 20th-century modernism more or less tuned it out. Yet in the last few decades artists, if not curators, have become more open to the subject…”²

Unfortunately, the onset of that “tuning-out” occurred precisely as North American Indians began coming into their own, in terms of conversion, and thus they were abandoned by the sophisticated art world as far as representation. Now more than ever, artists of faith in every discipline are justified in addressing this neglect of what is arguably the most difficult feat accomplished across the continent – the spiritual coercion of an entire race. Moreover, that representation should not relegate Native American Indians to mere conquests of elite and superior missionaries, but in accordance with the Scriptures which say of Christ: “…you ransomed people for God from every tribe and language and people and nation, and you have made them a kingdom and priests to our God, and they shall reign on the earth.” Wholly apart from any issue of “social justice,” spiritual justice demands their equal representation as sovereigns and savants – and saints.

Indigenous believers will find themselves well-represented at Giuliani’s sacramental “table.” There is only one, not very impressive, painting of St. Kateri drawn by one who knew her. So it is with more than a bit of wonder and consternation that, looking into his Mohawk Kateri III #92, it is as though I am gazing into the face of my own late mother, who was a direct descendant of an Algonquin born in the same generation as Saint Kateri, an Algonquin orphaned by the same smallpox which took Kateri’s likewise-Algonquin mother and Mohawk father. My amazement is not merely towards the actual features themselves, but the very attitude with which Father Giuliani has infused them. He has captured the soul of the Native American Indian with startling skill.

Saint Kateri’s expression is itself an embodiment of that stoic, borderline-suffering countenance which was my mother’s “thousand-yard-long stare.” Kateri is beatified by the beauty of a glinting bronze nimbus, full as a Beaver Moon, which was that calendar date of the “last call” for ancient Native American Indians to prepare for winter. It will appeal to the truly Indigenous, if only at an intuitive, vestigial level, signifying security amid worldly instability, recalling the ancestral memory of the beaver, symbol of that being who will provide warmth, our last and only hope and salvation by its sacrifice, keeping our hearts soft before the coming cold – a Christ figure from the Animal Kingdom, of sorts.

In the mythology of the Omaha people, we have in “Ictinike and the Four Creators,” a hero who visits a beaver which sacrifices its own son to provide him with food. Following this meal, the father beaver plunges the bones underwater, and the son is resurrected. Too, the Cherokee held a belief called “Cover the blood,” that an animal slain in hunting might be resurrected from its blood spilt by drops on the ground. A similar doctrine runs through the religion of many other tribes. ³

Could it be that, just as early Indigenous missionaries employed the touchstones of the “old religion” to woo their people to the Good News, Father Giuliani unwittingly or knowingly reconnoitered the Beaver Moon, for her halo? Saint Kateri is the patroness of Native American Indians and First Nations peoples, of integral ecology and traditional ecological knowledge, so whether by divine inspiration or his own carnal understanding, this would seem perfectly decided – almost, in fact, an environmental “election.” As Saint Paul wrote, “…to all men, I have become all things, that by all means I may save some,” such an artistic interpretation of Kateri’s nimbus has the power to draw and unite all Nations, from the Southeastern Cherokee who called the Beaver Moon “nu-da-de-qua,” to the Northwestern peoples’ “alangitapi.”

Rather than emphasizing a voluminous veil at her crown, Giuliani downplays the fabric around the saint’s face, focusing on copious, blue folds less suggestive of a cotton mantle than of “Long Man River,” who washed away the despair and impure thoughts of Native ancestors. The sheer weight and width of this massive, dramatic headdress seem to invite viewers not to the mystery fringe of a mortal woman’s hair, but to the currents of living waters. But whereas the veil and white sheath she wears reflect the traditional iconography of the “White Man,” at their lower edge is seen the familiar attire of Native American culture, where a multi-colored, zigzag pantaloon border grazes the tops of Saint Kateri’s dainty feet in moccasins. Her feet are firmly planted at a modest space, in a field of wildflowers where stands of lilies arise on either side, giving testimony to her designation as the “Lily of the Mohawks.”

But the covering of Saint Kateri’s hair proves a much more profound and powerful outward sign of devotion to the Native American Indian viewer, than it does to the non-Native. The covering of the hair conveys a submission to the Christian faith as well as a cultural “assimilation” in a manner that white European Christians could never fully experience, for hair is sacred in Native American Indian culture, a source of ornamental service especially in worship at ceremonial events. An Amerindian’s long hair represents strong self-identity, even clan affiliation (as in the Cherokee “Long Hair Clan”). To throw away our hair is to practice self-mortification, even mourning akin to the Old Testament practice of rending one’s garments, an utter disregard of the ego which goes far beyond the customary cutting of a nun’s hair (symbolizing an end to feminine vanity). Thus Saint Kateri gains profound universal reactions of renunciation through this imagery, humility which contemplative American Indians both male and female will feel in a visceral way.

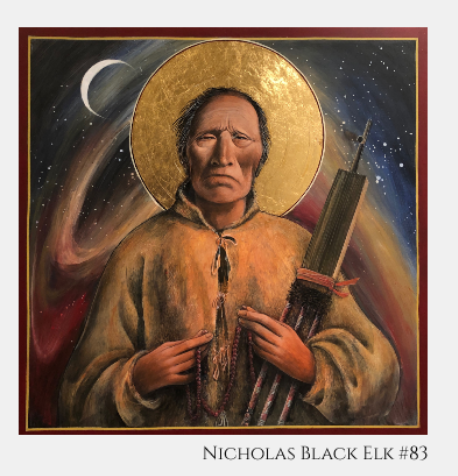

Also noteworthy in Giuliani’s “sacred Indian menagerie” is his iconography of the Lakota Holy Man, mystic and Catholic missionary, Nicholas Black Elk. While Black Elk is not officially a canonized saint, the Jesuits appointed him to the position of catechist after his baptism in 1904. Thereafter, Black Elk is credited with bringing hundreds of fellow Native American Indians into the faith. Devotions including the rosary and Sacred Heart were a vital part of his practices, thus it is perfect that Giuliani, in “Nicholas Black Elk #83,” has portrayed him with a strand of rustic and somewhat-crudely mismatched beads of natural wooden hue. While Giuliani’s use of lunar imagery might be debatable in the depiction of Kateri, here it is undeniable.

Behind Black Elk’s aureole, reminiscent of a hammered brass cymbal, a crescent moon hangs against the backdrop of a starry night sky. Punctuating the heavens, a celestial supernova swirls around his shoulders in orbits of streaked red and gold, giving the impression of enormous, interstellar wings. His face is un-romanticized and unerring in likeness to the mien of the one after whom it was modeled. There is no question that this is Black Elk as he appeared in the last years of his life. The illusion would be complete, except for the icon’s ragged monastic robe with its lowered hood, hidden behind the rough-hewn cloth of a garment whose yellow hues harmonize with the gold of the supernova “wings” on either side. This effect being so seamless, the viewer feels all the more that they are appendages, “feathered” outgrowths of the man himself. Again, here it seems there is more subtle symbolism at work, a hint at the antediluvian Birdman regalia of Native American Indians which elevated priests to their stature, conveying instant recognition at mere sight to every domestic clan and outside tribe.

Vestiges of this ancient diaconate are still visible today in the falcon dancer “vestments” seen at powwows for formal stomps and ceremonies. In the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, the Birdman represented the Upper World, where its genesis was accompanied by sun, moon, and stars – the latter two which also appear in Giuliani’s icon. “The life of an Indian,” said Black Elk, “is like the wings of the air… That is why the Indian is always feathered up, he is a relative to the wings of the air.”

If ancestral memory does indeed remain, passing down along with the “generational trauma” a hunger for and appreciation of unction both heavenly and carnal, then the Native American Indian viewer should find ample spiritual inspiration – and if not, Giuliani’s sublime suggestion of the ritual feathers is sufficient, imparting at least a dose of tangibility, reinforced through use of the red ochre and sunflower/corn silk yellow paints which were so common to the culture. The combination is found equally in authentic Buffalo Dreamer hand-painted rawhide shields and genuine turtle amulets on display nearby in the galleries of that Prairie Edge & Sioux Trading Post, authentic art by the Ute Nation and Oglala Lakota – Nicholas Black Elk’s own blood people.

Consequently, this priest’s art is art which has undoubtedly found its place. In a pastoral letter, Reverend Nicholas Black Elk wrote of the American Indians, “We all suffer in this land. But let me tell you, God has a special place for us when our time has come.” Surely if we read the signs and have ears to hear, that time has now come, with one of those special places living in the lasting works of John Giuliani.

Jennifer Reeser is a bi-racial writer of European American and Native American descent, the author of “Indigenous,” and “Strong Feather.” Her reviews have appeared in First Things, LIGHT, Able Muse, and elsewhere.

¹Despair Over The Pope https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2010/06/10/despair-over-pope/

2 Art Review: Creative Souls Who Keep the Faith of Challenge Its Influence https://www.nytimes.com/2000/04/21/arts/art-review-creative-souls-who-keep-the-faith-or-challenge-its-influence.htm

³History, Myths, and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokee, ©1900 by James Mooney, reprinted by Bright Mountain Books, 1992, p. 474