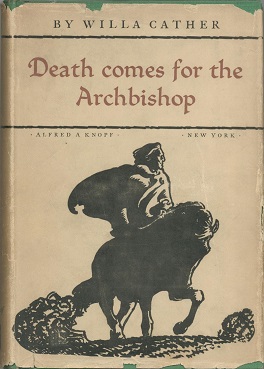

In spite of great differences, novelist Willa Cather and St. John Paul II show uncanny agreement as to the nature and validity of the Roman Catholic Church’s particular way of spreading the Faith to non-believers. Cather’s most successful novel, Death Comes for the Archbishop, reveals a vision of saintliness later codified in what JP2’s encyclical Redemptoris Missio calls “missionary spirituality.”

Cather was Episcopalian, not Catholic; Cather’s early success was in journalism, while St. Pope John Paul II excelled as a playwright, poet, and actor before choosing the priesthood; Cather was American, he was Polish; Cather’s birth in 1873 placed her in a century prior to both World Wars, and before John Paul II’s birth in 1920. However, the missionary spirituality which Cather demonstrated through her fictional skill in Death Comes for the Archbishop and which John Paul II articulated in Redemptoris Missio are the same.

Willa Cather’s novel, Death Comes for the Archbishop, originally published in 1927, was her ninth novel and one of her most enduring titles. In it, she presents the story of two French missionary priests, Bishop Latour and Father Vaillant, in the primitive and often dangerous nineteenth-century American southwest. They have made the difficult decision to travel across an ocean to bring Jesus Christ and His Church to unbelievers. The two friends encounter a range of desperate spiritual conditions in the people living in cultures acclimated to sin and violence. The list is long: apostate priests, murderers, pagan beliefs and rites, a “Catholic” culture that has largely withered and died for complicated reasons or has simply never been introduced.

Cather’s later comments reveal that she chose to write this novel with an emphasis on the eternal rather than the temporal. In an open letter to Commonweal about Archbishop, Cather wrote: “I had all my life wanted to do something in the style of legend, which is absolutely the reverse of dramatic treatment.” She continues by saying that since she viewed the Purvis de Chavannes frescoes of St. Geneviève as a schoolgirl she had wanted to write a piece “without accent”—a piece that would touch upon an incident, then pass on to others. Such writing would only be successful and integrated if there was a powerful narrative grander in scope that the quotidian urgencies of plot. Cather found her powerful narrative in the battle of Good against Evil.

Cather’s choice of missionary Catholic priests for the main characters of this novel is startling when viewed again the backdrop of her lived experience as a non-Catholic. Yet she had been visiting the Southwestern rural countryside and Indian villages for at least 15 years before writing the novel. Her typically terse conclusion was: “The story of the Catholic Church in that country was the most interesting of all its stories.” Cather chose not to write the dramatic story of missionary priests martyred in North America—a long list containing some deaths that were well-documented in journals and letters, such as the torture and death of 35 year-old Fray Luis Jayme, one of St. Junipero Serra’s fellow Franciscan priests, who was stripped, shot with 18 arrows, then beat about the head and face with stones and cudgels until he died. Instead, Cather wrote the daily stories comprising the decades of missionary service in a way that allows the reader to settle into the slow, plodding road to saintliness where the eternal significance of the characters’ actions and choices is what matters.

A close reading of St. John Paul II’s encyclical Redemptoris Misso, published on December 7, 1990, elevates Cather’s novel from a brilliant study in saintliness to a thorough and luminous study in missionary spirituality. With firm clarity, the document begins its chapter on “Missionary Spirituality” by stating: “Missionary activity demands a specific spirituality.” Next, the four main components of missionary spirituality are listed: a life of complete docility to the Spirit, intimate communion with Christ, apostolic charity, and the call to holiness.

The foundational characteristic of mission spirituality is defined as “. . . being molded from within by the Spirit, so that we may become ever more like Christ.” Upon this basis, the missionary builds his or her life to enable the work of bringing the Gospel to non-believers. The essential characteristics which flow from the life of docility to the Spirit are the gifts of fortitude and discernment. From intimate communion with Christ comes the two characteristics of a person’s total self-emptying and the overcoming of attachment to people and things. Apostolic charity brings both a love of people and a love of the Church. And, lastly, the call to holiness necessitates that a missionary be a contemplative in action as well as a person of the Beatitudes.

Cather’s novel gives numerous examples of the main characters displaying each of the four components of mission spirituality by letting the reader see Latour’s and Vaillant’s reactions to people and circumstances. Since the call to holiness is such a distinguishing feature of the two men’s lives, let’s see how Cather conveys it.

In the first scene of the book, Bishop Latour wanders lost and thirsty in a parched land with almost no hope of finding water. Latour doesn’t fear death, but relies on his faith that the Holy Spirit is leading him. The configuration of branches on a tree reminds Latour of the cross of Jesus Christ and without hesitation he falls to his knees to pray in meditation on Christ’s words from the cross: “I thirst.”

Cather allows the cruciform tree branches to bring allegorical significance and spiritual focus to Latour’s self-sacrifice and suffering. Latour’s reaction of abiding faith in God establishes the reader’s expectation that Latour will find the spiritual in the temporal events he encounters throughout the book, and he does. Even after the two later instances of spiritual doubt or dryness in the book, Latour returns to prayer and to God. In the aftermath of Latour’s close brush with death through dehydration and exposure, and in his miraculous discovery of water and food at a hidden oasis with good and humble people, we glimpse Vaillant’s own spirituality from his friend-since-childhood Latour’s perspective: “. . . his dear Joseph [Vaillant] must always have the miracle direct and very spectacular, not with Nature but against it. He would almost be able to tell the colour of the mantle Our Lady wore when She took the mare by the bridle back yonder among the junipers . . .”. The conclusion of both priests that a miracle occurred is steadfast, but their individual reactions illustrate their very different personalities: Vaillant is impetuous and unassuming, Latour is reserved and careful, and quiet, if not slightly pedantic.

Cather builds upon the unique personalities of each man to illustrate the other components of mission spirituality. In showing Latour and Vaillant as possessing both fortitude and discernment, Cather reaches into her writer’s toolbox to draw lively scenes and personalities of people with whom the priests must interact.

For instance, Latour’s quiet sense of when and how to act, or not act is one of his most intriguing qualities. How does he know, when viewing the rebellious Fr. Martinez whose “mouth was the very assertion of violent, uncurbed passions and tyrannical self-will” that “the day of [Martinez’s] lawless personal power was almost over”? How indeed? In a little over one year later, Martinez will formally resign his parish, and Latour will replace him with a Spanish priest that Latour recruited with the exact combination of skills and qualities to be accepted by the parish so they can be shepherded back to a correct understanding of the Faith. Fr. Vaillant possesses his own kind of discernment, which, due to his naturally impulsive personality often manifests in sharp bursts of friendship and goodwill. Cather records numerous successes where Fr. Vaillant makes friends and fosters thriving parishes even in areas previously under the magnetic sway of a rebellious priest banished by Latour.

Both priests possess the particular strength of character defined as fortitude by the Catechism of the Catholic Church: “the moral virtue that ensures firmness in difficulties and constancy in the pursuit of the good.” Fortitude encompasses bravery but goes further with its emphasis on an interior moral compass defined by God.

It is easy to find examples of both priests’ bravery in uneasy and hostile circumstances throughout the saga of their decades in America. But personal bravery alone cannot explain their calmness during all the threatening circumstances. Cather great literary triumph is to make the reader understand that there is a spiritual depth underpinning their preparation and bravery. They expect God’s will to unfold and are solid in their adherence to it. Their assured serenity in the face of danger and hardships reflects a commitment to accomplishing the moral good and their belief that God will use them for that end.

The total self-emptying in order to identify with Jesus Christ that is required by missionary spirituality refers to Phil. 2:5-9 where St. Paul refers to Christ’s self-emptying in order to effect both the Incarnation and man’s Redemption. Redemptoris Missio quotes the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council’s Ad Gentes which states: “the missionary is required to ‘renounce himself and everything up to this point he considered as his own, and to make himself everything to everyone.’”

While examples of the simple normal pleasures the two men have had to give up are spread throughout the novel (French pears, lettuce, beautiful vestments, Gothic cathedrals, green vegetables in winter, lamb cooked rare, sheets or beds, the emotional consolations of family), there are other deeper sacrifices.

Fr. Vaillant gives up his longing for a settled life of devotion to the Blessed Mother in a quiet monastery with no further travel to tax his frail physique; Fr. Latour, those intellectual pursuits where he experienced great success as a younger priest and their accompanying aesthetic rewards. Both men consciously choose to deny themselves what would best suit their natures in order to live out their missionary role under rough and unpredictable circumstances on a foreign continent. Neither of them grumbles nor questions the sacrifices. This patient endurance and embracing of hardship to save souls is testified to by North American missionaries, such as St. Junipero Serra writing after years of hardship upon finding out that supply ships were disastrously late in arriving to the bay of Monterey in 1772: “All the missionaries grieve—we all grieve—over the vexations, labours, and reverses we have to put up with. No one, however, desires to leave his mission. The fact is, labours or no labours, there are several souls in heaven from Monterey, San Antonio, and San Diego.”

Missionary spirituality demands two types of self-renunciation which are themselves components of asceticism defined by the Church as “the disciplining of the will.” The first is self-renunciation against all temptation to “self-seeking, self-promotion and self-indulgence.” The second is asceticism related to the ministry to others, such as the inconveniences of missionary travel, disappointment, opposition, and the misunderstanding of co-workers.

All of the priests in Cather’s novel could be evaluated according to these standards, with some living up to these standards and some not. But it is Vaillant and Latour whose tireless work to save souls is foregrounded. The extrovert Vaillant has single-minded, boundless energy and enthusiasm for each new assignment in spite of his broken body and numerous injuries and brushes with death. Latour’s “self-renunciation” related to his ministry is best seen in his miles of arduous horseback and mule-back travels to learn about the various types of people in his diocese so he can appoint priests who will be most effective in the widely different locations. More than once, Latour and Vaillant are observed to be working as hard as parish priests despite the fact that they are respectively, bishop and vicar. These scenes in the novel remind the reader of the hard-working and apparently tireless St. Junipero Serra who routinely walked up to 35 miles/day with a painful, ulcerated leg to reach more souls who hadn’t heard the saving word of God. This same zeal to minister to souls for their salvation is articulated in the writing of St. Serra about the reasons for establishing the Franciscan missions: “Above all, let those who are to come here as missionaries not imagine that they are coming for any other purpose but to endure hardships for the love of God and the salvation of souls.”

The ability for self-renunciation illustrated by these examples both in the novel and in historical letters and journals of actual North American missionaries is complemented and completed by a quality the encyclical calls “apostolic charity.” The encyclical continues: “The missionary is urged on by ‘zeal for souls,’ a zeal inspired by Christ’s own charity, which takes the form of concern, tenderness, compassion, openness, availability and interest in peoples’ problems”. This apostolic charity is rooted in Christ and his love for both men and his Church. The encyclical continues with foregrounding the missionary’s necessary love for Christ’s Church.

Throughout the novel, Cather shows both priests responding to the needs of complete strangers with a complete disregard for their own comfort or safety. Without hesitation, Vaillant journeys through a storm and negotiates the dangers of washed-out roads and darkness to give Last Rites to Padre Lucero, an apostate priest who previously undermined Latour’s authority as bishop. Once he arrives at the deathbed location, Vaillant stays true to his “zeal for souls” by focusing himself, the dying man, and everyone else in the house on Padre Lucero’s salvation and the proper disposition of a dying man’s soul.

Religious novelists have often discussed the “face of God” problem, the difficulty of showing through the natural world the supernatural realities. The extraordinary gifts of Willa Cather have offered this alternative: a realistic and profound glimpse into the face of a saint. At the novel’s conclusion, the reader is left with an appreciation of two men whose lives have been depleted totally by the hardships of their missionary work. Yet both men are presented as content despite the pain of old injuries and the deprivations of their existence in America. This is the peace of God which passeth all understanding.

These two priests have wholeheartedly fulfilled their role as missionaries, so beautifully drawn in Cather’s prose and summarized by another saint—St. John Paul II—in Redemptoris Missio.

Sarah Cortez is president and founder of Catholic Literary Arts, www.catholicliteraryarts.org. A freelance writer and editor with fourteen award-winning books, spanning poetry, fiction, essay, and spiritual memoir to her credit, she resides in Houston, TX. www.poetacortez.com