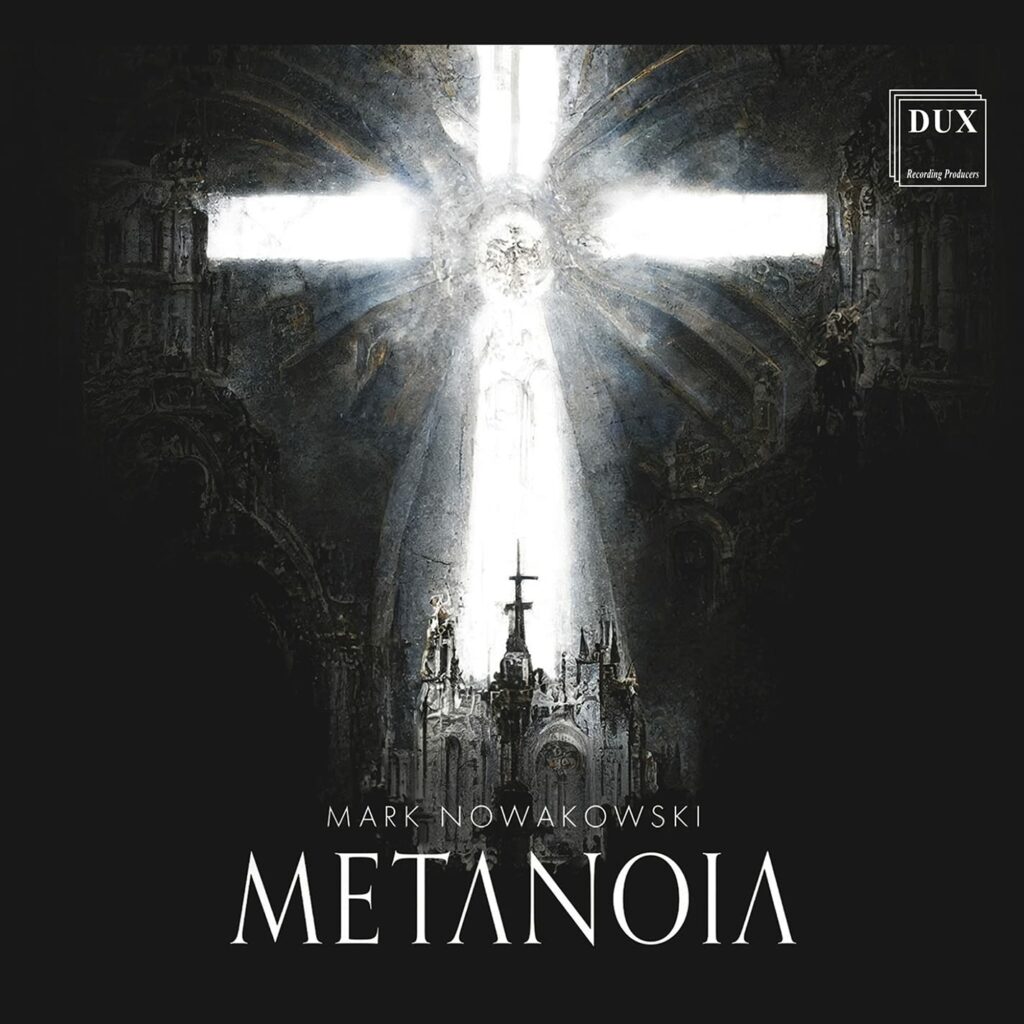

On May 19th I’ll be releasing my second album, Metanoia, published by the Polish label “DUX” and distributed internationally via Naxos. This is the story of a composer’s journey in creating new sacred music that brings people closer to God.

What is sacred music? This is the first question I wrestle with, for while the line between liturgical and non-liturgical music is at least somewhat clear, the question of what makes music “sacred” drifts into more fraught philosophical territory. Music itself points towards transcendent striving and the music most fully realized is one which engages our contemplative nature. Sacred music is that which makes us stop and contemplate what lies beyond the noise and distraction of the world: It points us toward God.

Even during a time of growing hostility to faith in general and Catholicism in particular within the concert hall, it is the works of Catholic and Orthodox composers which have continued to play a major part in our classical music.

The 20th century’s greatest composition pedagogue, Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979), was a deeply faithful Catholic and daily communicant, and most of her famous students (even those not implicitly Christian) retain a distinctly spiritual approach to their work.

One of her many contemporaries was Olivier Messiaen (1907-1992), a French composer whose compositions are marked by his Catholic faith and fascination with theology. Some secularists love his fascination with birdsong (which I suspect for Messiaen pointed to the universal harmonies of the Creator anyway). I rather prefer his Poèmes pour Mi, which strikes me as a historical musical prelude (and musical counterpart) to the deep theological meditations of John Paul II’s Theology of the Body.

Francis Poulenc’s (1899-1963) many sacred works, including his Gloria and Stabat Mater, reflect his deep spirituality and commitment to the Catholic Church. In midlife, when a dear friend died in a traffic accident, Poulenc made a pilgrimage to the Sanctuary of the Black Virgin in Rocamadour, triggering a profound spiritual revelation. His resulting Litanies for the Black Virgin for women’s chorus and organ was premiered by Nadia Boulanger during a London BBC concert.

Henyrk Górecki (1933-2010) was another Catholic whose works include luminous choral works and the best-selling Third Symphony, yes, but also a grouping of more challenging chamber works which invite deeper contemplation. (I’ve written about them here.)

Giya Kancheli (1935-2019) was a devout Orthodox Christian born in Soviet Georgia whose striking works, including his Liturgy for Viola and Symphony No. 6, are characterized by their meditative quality and evocative use of soundscapes. John Tavener (1944-2013) was an English convert to Orthodox Christianity. His masterworks include the record-setting The Protecting Veil and haunting Funeral Ikos.

Today the heirs of this line of composers include Arvo Pärt (Orthodox, but setting almost exclusively Catholic texts), and Sir James MacMillan. MacMillan’s compositions reflect his Catholic faith and Scottish identity, with works such as his St. John Passion and Symphony No. 5 receiving critical acclaim, though it is his Confession of Isobel Gowdie and his Sing a New Song which move me most profoundly. Pärt’s minimalist style is infused with religious motifs, evident in works such as his Magnificat and Tabula Rasa.

In Poland, Pawel Lukaszewski holds a dominant role among composers, and I think succeeded in his astounding Via Crucis in writing the first sacred masterwork of the 20th century. Lukaszewski in turn has inspired composers like Sebastian Szymanski, who writes truly gorgeous music. Finally in North America we have our own Frank LaRocca, who is leading a new generation of Catholic composers in various stages of their career including Jeffrey Quick, Daniel Knaggs, Bobby Chastain, Xanthe Kraft, and others.

The next generation of Catholic composers should take heart: despite the hostility we encounter, both the origins of our craft and its modern manifestation are distinctly Catholic by nature, and I would go as far as to claim that a Catholic art needs a Catholic perspective to be most fully realized.

As to my own part, In my 2017 release for Naxos, Blood Forgotten, the string quartets featured within were deeply personal statements (as many string quartets are) and represented some of my most heady and complex music (as many string quartets do). There are rich statements of culture and philosophy here, yes, but also distinct moments that reach for the sacred in music. While the album was successful, a number of other diverse projects were already brewing, from chamber to choral to even electronic music. Over a period of eight years I collected the best recordings from these various collaborations, intent on assembling them into a distinctly Catholic vision of non-liturgical sacred music. I hope to craft and share music which challenges the listener and takes them on a journey, or perhaps provides contemplative fodder for their own spiritual journey. From this my second album, Metanoia, has been born.

The title track, “Metanoia,” was a collaboration with the Italian-based Monteverdi Cello Octet, with whom I developed an immediate connection despite the geographical distance between us. The piece explores the Gospel meaning of the Greek word “Metanoia,” which is often translated as “repent,” but in reality carries the deeper command to “change one’s manner of thinking.” There is difficulty of changing ingrained thoughts and habits, yes, but even more profoundly there is great struggle to change spiritual habits and enliven dead hearts; music for its part is the ideal vehicle with which to explore and express these often indescribable spiritual struggles.

Metanoia begins with strained and uncertain textures and builds into a rich melodic landscape before arriving at a place of fierce conflict. Eventually, the conflicting lines settle into an aggressive percussive repetition, while a new pleading melody emerges, threatening to explode into ecstasy before descending into a more uncertain ending: the journey goes on, as we have “put into the deep,” but Christ is with us, and our fundamental transformation continues.

It’s the most challenging work on the album and intentionally put first on the disc: This is contemplation, not easy listening.

We travel from Italy to Poland next with “Tu autem, Domine?” which is a gentler work, a meditation for mixed chorus that repeats and refashions its short text into a series of varied spiritual questions, which seem as much a plea as an impassioned demand. The questioning ultimately settles into a dramatic “Amen,” vacillating between uncomprehending resignation and peaceful acceptance. I explored the particular way that Poles approach God in our personal and historical difficulties in this work, which was beautifully brought out by Szymon Wyrzykowski and his wonderful “Chaps” choir in a recording session in Szczecin, Poland.

The album proceeds to “Before I formed you…,” a work for voices and baroque stringed instruments, arising from my frequent collaborations with Three Notch’d Road and violinist Fiona Hughes and bass-baritone Peter Walker. As a father of four, the meaning of this work is far from ambiguous for me, and our premieres with Three Notch’d Road featured Catholics pensively approaching me to see “if I really meant what I think you meant.” Indeed, I did. After all, I’ve had the privilege of witnessing beautiful little humans – full of personality and complexity – manifest into our universe, challenging and enlivening us with their precious presence.

To think of what this means, and how God cooperates with mere humans in the begetting of eternal beings, is a shattering reality that I wished to contemplate in this new work. The piece takes its text from Psalm 139:13-15, announcing “For thou didst form my inward parts,” and slowly growing in intensity as they declaim: “thou didst knit me together in my mother’s womb. My frame was not hidden from thee…”. The music takes a fragile and introspective turn with the singers stating: “when I was being made in secret, intricately wrought in the depths of the earth.” If the preceding words can be understood as an individual’s praise for their own creation, the reply from Jeremiah 1:5 is perhaps God’s answer. The strings transition into a modern and sparse sustaining texture as the singers state in unison “Before I formed you in the womb, I knew you,” at which point the sustain buzzes and grows with the words “and before you were born I consecrated you.” The piece is bookended by a variation of the opening string duo, a musical ellipsis implying the continuation of life’s drama beyond the musical expression itself.

All sacred music, properly understood, is prolife, but this hymn happens to use the same Biblical quote Archbishop Cordileone used to title his letter on the Eucharist, abortion and Communion.

Listen here:

The piano trio Reaching moves from mysterious textures to rampaging exchanges, pushing the University of Memphis Trio to their limits. Metaphorically, the piece is about “crabs in a bucket,” or a story that fishermen tell. When one of the crabs closer to the top sees the light and tries to escape, the other crabs reach up and pull their intrepid colleague back down. The moral of the story, of course, is that “people are like crabs in a bucket.” Anyone who strives to break the mundane will struggle through such things in their own life, and often we are dragged back down despite our best efforts. In such moments a repose is necessary, a re-gathering of strength, a prayer, and a renewed ascent begins.

Quo Vadis, Domine? is a 20-minute sacred drama set on the famous story from the early days of the Church, as famously dramatized towards the end of Henryk Sienkiewicz’s novel Quo Vadis. As a libretto, I set the very words of the scene from Sienkiewicz’s novel into a dialogue form, after which they were translated into Latin by a priest-scholar from the Confraternity of St. Peter (FSSP). Individual singers represent the characters in the story: Peter sung by countertenor, his boy traveling companion by soprano, and the words of Christ by Peter Walker’s resonant bass-baritone. When singing as a trio, the ensemble represents the narrator. This ancient economy of means allows for expansive storytelling, and if a poem can bring deeper spiritual insight and focused intensity into a minute event or observation, then music has the added advantage of also stretching out the emotional and contemplative material of such an encounter into temporal time.

The album concludes with Bogurodzica: Medytacja (“Mother of God: Meditation”) a work for cello duo and electronics which takes as its source material the famous Polish hymn of the same name. The initial low antiphonal exchanges between the cellists allow the electronically generated accompaniment to subtly enter, ushering in a rich tapestry of sounds almost entirely drawn from digitally manipulated recordings of the cello. It is, in many ways, a companion work to Blood, Forgotten, for solo violin, video and electronics, the title track of my debut 2017 Naxos release. I know that some listeners will see the words “cello and electronics” and flee, but it was my intent to go against the grain of so much pointillistic and unapproachable electronic music, and instead write something moving and beautiful where the cello – not the computer – takes the lead. There is a challenging contemplative arc to the piece, but my hope is at the end of this album, Bogurodzica will leave the listener in a timeless and expansive place.

As a Catholic composer, I hope that this work will inspire others to seek transformation and to embrace the challenges and opportunities of the spiritual life.

Composer Mark Nowakowski’s latest work Metanoia is available here: https://naxos.lnk.to/DUX1916