There couldn’t be a work of literature more “medieval” than Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy. It’s suffused with the scholastic philosophy of the late Middle Ages, it’s as schematically constructed as a Gothic cathedral, and it moves methodically through a precise theological geography of the afterlife—hell (“Inferno”), Purgatory (“Purgatorio”), and heaven (“Paradiso”) —that even many Catholics have trouble believing in these days. And yet, in our resolutely secular age that seems the opposite of medieval in its rejection of divine rewards and punishments and its strict hewing to the here-and-now—the Divine Comedy, completed shortly before Dante’s death in 1321, is the second-most translated work of literature after the Bible. The bad Dante-themed Tom Hanks movie Inferno (2016), based on a bad Dante-themed Dan Brown novel Inferno (2013), was actually a worldwide box-office hit despite boos from the critics. Something about the Divine Comedy resonates.

And what resonates is the modern conviction that although heaven and Purgatory might be the wishful creations of a credulous bygone age, hell—the Inferno—is still to this day all too real. Especially Dante’s hell. Dante constructed his Inferno in precise mathematical dimensions—nine descending circles featuring successively worse punishments for sins deemed successively worse, and culminating in the spectacle of Judas, condemned for all eternity to be chewed by the teeth of Satan, The latter is an enormous bat-winged, half-frozen monster occupying hell’s icy-cold nadir whither all warmth and love have long ago gone to die. At the same time that he created these horrifying visions, Dante peopled his hell—as well as his Purgatory and his heaven–with real historical people, some of whom were his own contemporaries. A native of Florence born in about 1265, he had taken the wrong side in Florence’s byzantine political cross-maneuverings, and in 1302 he had been exiled from the city on pain of death. He composed the Divine Comedy mostly in Ravenna, the Adriatic city where he eventually landed and spent the rest of his life in exile. Some of Dante’s real-life characters are lovely, notably Beatrice Portinari, the beautiful fellow Florentine whom he loved and idealized from afar although the two were married to others; she is his guide to Paradise.

But the most vividly realized were the real-life sinners Dante consigned to the circles of hell, assigning them ghastly but condign punishments he called Contrapasso: suffering the opposite of what they fancied themselves to be at the height of their sinful pride. There’s Filippo Argenti, a rich and nasty-tempered political persecutor of Dante back in Florence whose brother was said to have seized Dante’s house and appropriated his possessions after he fled the city. Argenti ends up in the Inferno’s eighth circle, confined to a bog where he weeps and compulsively gnaws at his own flesh. Another wicked Florentine, Guido da Montefeltro, became a consigliere to Pope Boniface VIII (r. 1294-1308), whom he (according to Dante) advised to enter into a fake truce with his enemies (the rebellious city of Palestrina, part of the Papal States) and then slaughter them as they emerged from their fortress. Guido also ends up in hell’s eighth circle, perpetually burning in a mighty flame reserved for evil counselors. Suicides—self-murderers–are punished by being encased in trees to be pecked at by harpies. The once-beautiful prostitute Thaïs, who sold her favors to Alexander the Great, among many others, writhes in excrement and sewage.

This is the sort of evil—fraud, greed, treason, murder–persistent to this day, that you don’t have to be a Christian believer to find compellingly deserving of violent eradication. Add to that the sheer palpability of the punishments that Dante visits upon its perpetrators in the Inferno. It is not surprising that while Purgatory and Paradise may seem fantastical to today’s secular moderns, they can see Dante’s hell all around them.

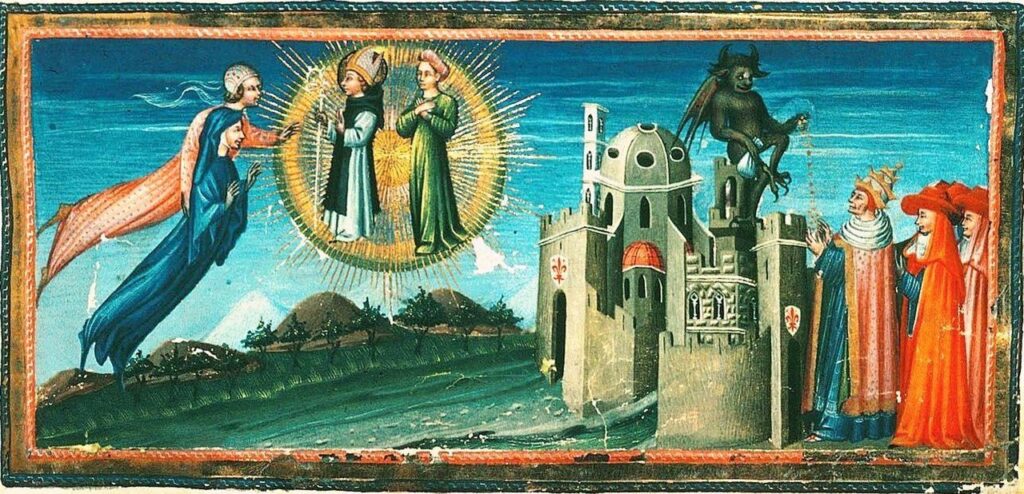

So when, a few weeks ago, I visited an ongoing Dante exhibition at Washington D.C.’s National Gallery, promising to survey artistic takes on the Divine Comedy from the Renaissance to the present, I wasn’t surprised to discover that the subject matter of nearly all 20 of the works, drawn from the National Gallery’s own collections, was exclusively the Inferno. Indeed, the exhibition’s curators bluntly titled it “Going Through Hell.” This wasn’t so in Dante’s own age. The fifteenth-century Sienese painter Giovanni di Paolo illustrated a manuscript of the Paradiso with glorious, brilliantly colored renderings of a graceful Beatrice leading Dante through the nine concentric circles of heaven, their serene geometry offsetting the screams and chaos of the Inferno’s nine circles and offering a compelling vision of divinely ordered harmony in which even the lowliest animals have their place in creation.

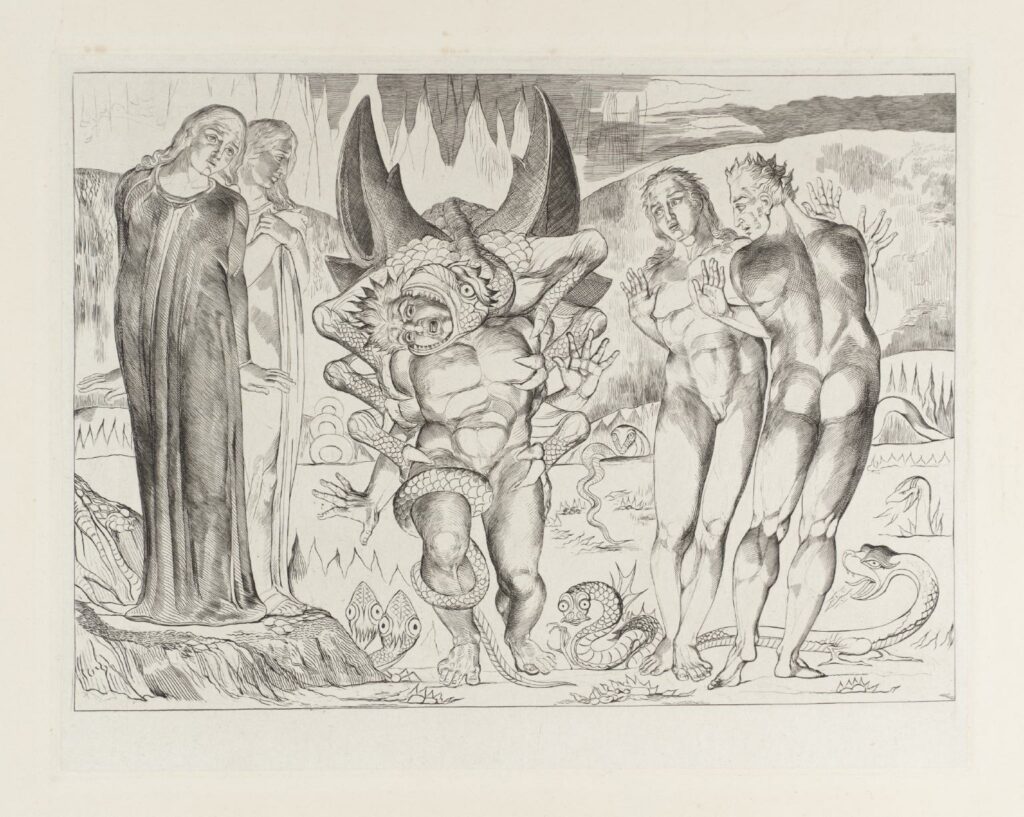

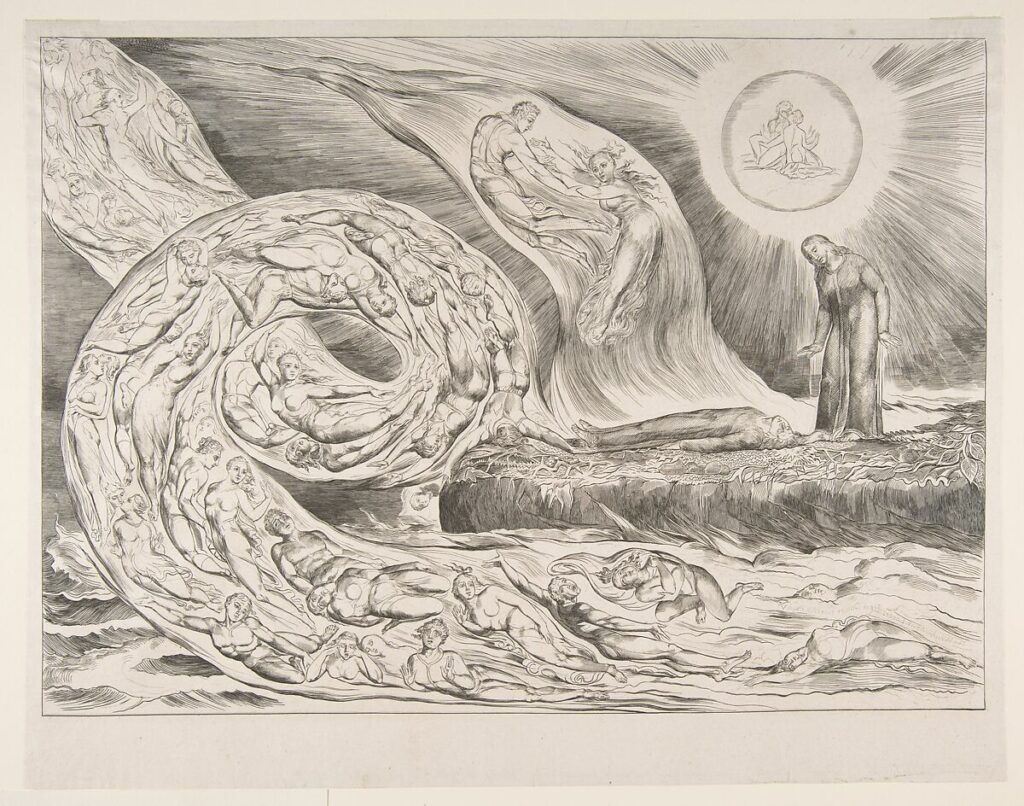

But it seems that artists of more recent centuries prefer to focus on unredeemed sinners suffering their gruesome punishments instead of on a heaven they cannot believe in, or on Dante’s Purgatory, a steep and penitential mountain to be climbed by sinners who die in repentance. William Blake, working during the 1820s on a never-completed project of making watercolor illustrations for the Divine Comedy, was mesmerized by the fate of Agnolo Brunelleschi, a notorious robber condemned to the Inferno’s seventh circle, where he is perpetually devoured by a six-footed serpent, which, in Blake’s line-drawing, actually melds its body with that of the half-eaten Brunelleschi, During the 1880s Gustave Doré produced a series of engravings for the Divine Comedy that probably include the most frightening visualizations ever made of Dante’s hell. In Doré’s illustration, even the generally impassive Virgil, Dante’s pagan-poet guide to the underworld, looks abashed as he and his companion survey a scene of popes punished for committing simony: selling their holy office and its privileges. The popes—and there seem to be at least a dozen of them–are plunged head-first into a molten lake, so that only their bare legs protrude so that the soles of their feet can be perpetually burned with flames.

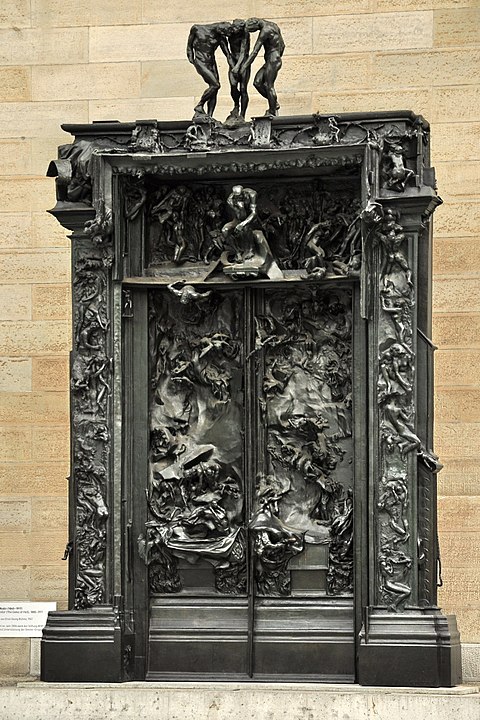

It’s surprising to learn, as I did at the National Gallery, that some of the most iconic bronze sculptures of August Rodin are actually illustrations of the Inferno. Rodin’s “The Thinker” (modeled in 1880, cast in 1901), the muscular nude man with his head pensively bowed, was meant to sit atop a pair of bronze doors conceived as the gates of Dante’s hell (“abandon all hope”) and featuring other nude figures in torment.

Similarly, Rodin’s “The Kiss” (modeled 1880-1887, cast 1898-1902), the nude man and woman embracing passionately–is actually an illustration of Dante’s story of Paolo and Francesca, real-life Florentines of the late thirteenth century. Francesca was married to Paolo’s brother, and while he was off at war, the two young people left alone together fell in love. When the brother returned and caught the pair in flagrante, he killed them both. Dante consigned the murderous brother to one of hell’s lowest circles, but the punishment he meted to Paolo and Francesca was, although eternal, relatively light: to be blown about by the winds of their lust in the Inferno’s temperate second circle. Paolo and Francesca appealed to nineteenth-century Romantics, who tended to view them sentimentally, not as adulterous sinners but as star-crossed lovers. Blake, like many other artists of his century, had also produced a version of Paolo and Francesca—and he, like Rodin, had focused on the characters and their emotions rather than on the story’s moral lessons. Blake’s 1827 drawing, at the National Gallery, depicts Dante himself as lying on the ground supine with pity for the unfortunate pair.

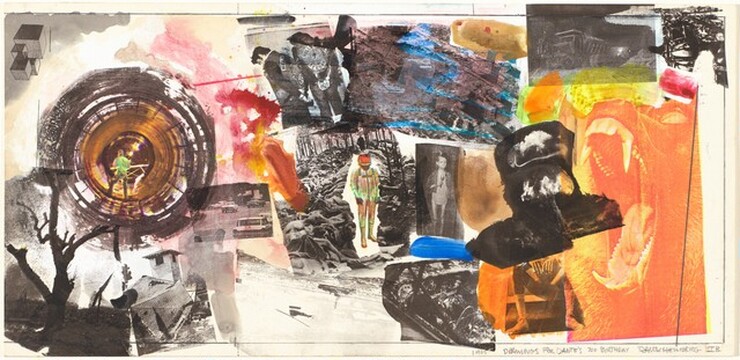

This focus upon the earthly circumstances of the sins themselves rather than the fates meted out to them by divine justice, is most evident in the chronologically last item in the National Gallery exhibition: mid-century Pop-artist Robert Rauschenberg’s 1965 “Drawings for Dante’s 700 [sic] birthday.” Earlier, starting in 1958, Rauschenberg had made a series of transfer drawings, using magazine photos as well as his own watercolor images and illustrating each of the Inferno’s 34 cantos in a translation by the poet John Ciardi. The 1965 artwork, similar in tone, is a collage of images from Life magazine: a mass grave, a starving child, a glut of flashy cars, belligerent Hell’s Angels wearing their club jackets. It is Rauschenberg’s hell on earth: violence, hunger, pointless consumer frenzy, the next war looming on the heels of the barely finished World War II.

Powerful as these images may be, what these artists of secular modernity seemed to have missed was that the Divine Comedy isn’t just a tour guide to the geography of the medieval Catholic afterlife. It is the story of a soul, Dante the narrator, who begins the poem by finding himself lost in a “dark forest” while he is “midway upon the journey of life.” It is a personal rather than a theological journey, which may be the reason Dante populated his afterworld with real people and chose to write his verses in Tuscan Italian, the spoken language of his living contemporaries, rather than scholarly Latin.

So it was a satisfying experience for me to turn to Toronto Catholic author Randy Boyagoda’s 2021 novel, Dante’s Indiana, whose witty title promises—and delivers—a satirical but ultimately serious look at a man’s (in this case a beleaguered, faith-struggling ex-college professor’s) efforts to work his way through a forest of hells both private and social. The professor in question, Prin, of Sri Lankan descent like Boyagoda himself, is teaching English at a struggling Catholic college when he accepts a junket to a wealthy mid-Eastern country with which the college hopes to partner in order to save itself financially. Along on the trip is the now-married Prin’s still-alluring former girlfriend, and he finds himself playing Paolo to her Francesca. A terrorist’s bomb explodes, killing the girlfriend and also the hoped-for mid-Eastern partnership. The college promptly folds, forcing Prin into early retirement and transforming its premises into an assisted-living facility where its former faculty members eke out marginal livings teaching “lifelong learning” classes to the resident seniors. Prin’s wife, Molly, outraged at her husband’s infidelity, moves herself and their four daughters to Milwaukee and acquires a Mormon boyfriend, an equanimous-tempered fellow who explains to Prin that he has already prayed him by proxy into Mormon heaven. Hoping to lure back Molly, Prin extensively renovates their Toronto home and runs through his entire savings paying for a swimming pool in the back yard that he thinks will make them happy. Prin needs a job.

And he finds one, working as a Dante consultant (although he knows next to nothing about Dante) to Charlie Tracker, an evangelical industrialist and amateur Dante enthusiast in economically distressed Terre Haute, Indiana, who plans to convert a pair of defunct athletic stadiums into a Divine Comedy theme park. The park, a down-market Disney World, will feature an Inferno and a Paradiso (no Purgatorio, since evangelicals don’t believe in Purgatory), with devil and angel cosplayers and suitable rides (in the Inferno, nausea-inducing whirling teacups and a roller-coaster in the shape of Geryon, one of Dante’s hellish monsters).

The Terre Haute of Boyagoda’s imagination bears an unfortunate resemblance to today’s real Terre Haute: a de-industrialized sad sack of a Midwestern city where, as Boyagoda describes it, the economic base, once thriving factories, now consists of “treatment centres, retirement homes, prisons, and retraining programs.” Drug addiction, mostly to opioids, is rampant, and Boyagoda describes an entire generation’s worth of ghostly, burnt-out addicts flitting among their still-sentient elders like the figures of the damned in Dante’s hell. Tracker’s plastic-packaging company, once a major employer, is on its last legs as the market vanishes for the CD covers that were its staple product. Tracker’s go-get-em son, “Just Call Me” Hugh, plans, with help from some foreign investors, to revive the dying factory by making blister packs for…yet more opioids, this time Chinese-made. To Prin, whose family life is shattered and whose Catholic faith is already hanging by a thread, the scene is a living embodiment of the Inferno itself. “Abandon all hope” is an apropos motto.

But Dante’s Indiana, like Dante’s own masterpiece, is a comedy, and not just in terms of its spot-on humor. but in the sense that Dante meant—a drama that ultimately ends in the restoration of harmony. Neither Prin in his personal life nor the factory workers struggling to deal with the declining economic fortunes and their offspring’s addictions can make a heaven out of the hell they live in. But they discover that they can make it a Purgatory, where life is hard but hope subsists. Prin and Molly begin to repair their marriage, and there is a conflagration at the end that may resemble the Inferno but may also represent the beginnings of the Purgatorio that the Trackers had tried to suppress.

Dante’s theology, drawing on the philosophy of Aristotle as mediated through the medieval Scholasticism of Thomas Aquinas, rests on the premise that human beings are created toward an end, a final perfection of their natures that in Christian terms is pure bliss, the face-to-face contemplation of God for all eternity. This is something that was hard to understand even in Dante’s faith-saturated age, when, as the real-life denizons of his Inferno amply demonstrate, it proved far too easy to be deluded by worldly wealth, power, and pleasure. Right now, with faith at an ebb, it is almost impossible to believe that anything exists beyond the hells that we humans can all-too-readily create. But the Divine Comedy, which is much bigger than the Inferno, persists in surprising popularity. Those who read it to the end may find, as Randy Boyagoda’s characters do, that just beyond the despair and misery that our age has created lies the possibility for experiencing joy.

Charlotte Allen is executive editor of Catholic Arts Today.