On June 26, 1941, in Soviet Ukraine, Father Mykola Konrad headed toward the forest outside the tiny village of Stradch to hear a sick woman’s confession. On the way back home, Fr. Konrad and his choir director Volodymyr Pryjma were detained by Soviet agents. A week later, their bodies were found stabbed repeatedly by bayonets.

Then as now the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church accounted for only a small minority of Ukraine’s Christians (about 4 million out of 27 million currently). Unlike the more compliant Russian Orthodox Church, however, the Ukrainian Greek Catholics were in communion with Rome and also answered to no earthly government. Beginning in 1939, the Soviet Communists confiscated Catholic property, seized Catholic schools and hospitals, and shut down Catholic presses and religious educational institutions. The Soviets first goal was to convert Ukrainian Greek Catholics to good Communist atheists. But if that failed, the second best thing was to get Catholics to renounce their allegiance to the Pope and adopt Russian Orthodoxy.

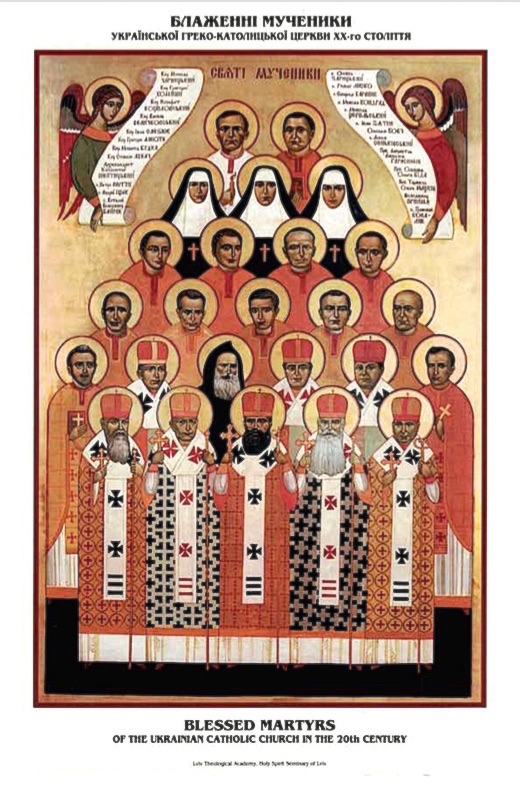

Konrad and Pryjma were among the first of 28 Ukrainian Greek Catholic men and women beatified as martyrs by Pope John Paul II in 2001. They were murdered outright or died of the effects of torture and deprivation while in the prisons and labor camps. One was crucified; another was reportedly boiled in oil while imprisoned, and a third said to have been sealed up in a prison wall.

Nearly all were priests and bishops except for three nuns and Pryjma as the sole layman. The Communists sought to terrorize leaderless Catholics into submission.

Today is a good day to remember the Ukrainian Martyrs in our prayers. But Communism has made Christian martyrs everywhere that it has seized power: Russia, China, Poland, the former Czechoslavakia and elsewhere.

The Church honors martyrs and saints under national titles, for the most part “the Vietnamese martyrs” the “North American Martyrs” “the Ukrainian martyrs.” Fair enough. But for a period of about 70 years there were worldwide persecution propagated by tyrants inspired by a deadly international ideology. The stories of Christ-like heroism in the face what can look like inexorable state power that cannot be ultimately defeated by state torture and murder are many. True these are national Catholic heroes and saints. But they deserve to be remembered under another title as well: Martyrs of Communism.

Here are a few of those stories.

Josef Toufar: The Czech Youtube Martyr

On a chilly Sunday morning, December 11, 1949, Father Josef Toufar mounted his pulpit in the tiny Czech village of Čihošt outside of Prague to deliver an Advent sermon. Behind him, parishioners reported, the crucifix above the tabernacle on the altar began to move from side to side. Father Toufar never saw the “Čihošt miracle,” as it came to be called, but the parishioners spread the word, and within weeks Fr. Toufar’s Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary became a place of pilgrimage. In Communist Czechoslovakia, that made Fr. Toufar a marked man.

In January 1950, the police arrested Fr. Toufar and transported him to the Czech prison at Valdice, then as now a grim maximum-security facility. Their goal? Make Fr. Toufar confess that he himself had rigged up the crucifix to move, via a hidden rope that he had supposedly pulled from the pulpit.

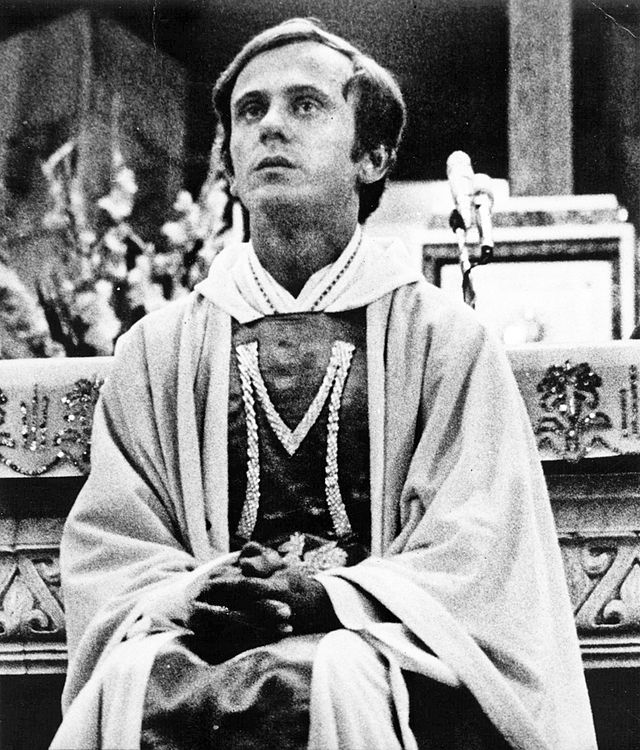

Fr. Toufar denied it. The guards then brutally beat and tortured him for four straight weeks, until finally he signed a prefab confession. Then, the police drove Toufar back to his church to star in a 13-minute documentary that included a purported re-enactment of the purported fraud. The black-and-white, obviously Hollywood-inspired propaganda movie, which can still be seen on YouTube, is a rare visual record of a martyrdom taking place in real time.

Viewers can see Fr. Toufar standing (or, more likely, propped up) in his pulpit, hastily dressed by his captors in liturgical vestments (he is missing the chasuble)—but also that his face and hands are swollen from multiple beatings and he looks barely sentient. The camera lingers on the postulated rope-and-pulley device, supposedly hidden behind a vase of flowers (an unlikely altar adornment for a Mass during the penitential season of Advent) and then the rope extends in cartoon form down to Pope Pius XII in Rome and from thence across the Atlantic to a Monopoly-board tycoon figure on “Wall Street” ultimately pulling the strings.

Two days later, Father Toufar died of his injuries. His body was dumped into a mass grave in a Prague cemetery under a fake name, and the movie that made him a figure of ridicule was shown to young people across the country.

Today, Father Josef Toufar, supported by the Czech bishops’ conference, is a candidate for beatification. His remains were exhumed and given an honorable burial in 2015, and his parish church at Čihošt is again a pilgrimage. Father Toufar is, of course, only one of tens of thousands of Christians murdered, executed, or tortured to death in nearly every country in the world where Communists have seized power—because Communism cannot tolerate allegiance to a kingdom that is not of this world.

Camilla Kruczelnicka: “The New Martyrs of Russia”

The Russian Orthodox Christians bore the chief brunt of the vicious systematic clampdown on Christianity that began as soon as the Lenin seized power in October 1917. An estimated 106,000 Orthodox clergy and monastics were killed in Stalin’s Great Purge of 1937-1938 alone; the Orthodox Church honors them as the “New Martyrs” of Russia. But the Catholic Church also had its share of “new martyrs.” We have documented evidence of around 1,900 Roman- and Eastern-rite Catholics who were shot or died in Soviet prison camps from 1918 to Stalin’s death in 1953. In 2002 the Russian Federation’s Catholic bishops’ conference launched a program to promote the beatification of sixteen of them.

Nearly all were priests or bishops, but the list also includes two nuns who died after lengthy prison sentences, and a laywoman, Camilla Kruczelnicka. Her story is remarkable. In 1933 Camilla was sentenced to ten years in the cruelest and most inaccessible gulag in the Soviet archipelago: the Solovki prison camp on an island in the far-north White Sea. Her crime was hosting clandestine religious discussions among Catholics in her Moscow apartment. In the prison camp, she married another inmate, but her new husband turned out to be an informant for the prison administration: he turned her in for attempting to contact Catholic priests among her fellow prisoners. On October 27, 1937, she was taken to a swamp near the Finnish border and shot.

Beda Chang: “Shanghai’s ‘counter-revolutionary mental bacteria’”

Shanghai, a center of Chinese Catholicism since the 17th century, has also been a focus of Communist persecution of Christians. Ignatius Kung Pin-Mei, the first native-born bishop of Shanghai, spent 30 years in prison until his release in 1985. The current bishop of Shanghai, Ma Daquin, has been under house arrest since 2012 after breaking with the party-approved Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association. And the area around Shanghai is the most likely location of one of the most beautiful stories of martyrdom under Maoism: the little girl, called “Li” in some accounts, who slipped into her parish church after dark each night to consume a Host from a ciborium that had been thrown onto the floor in an act of post-revolution desecration. The night she consumed the very last Host, one of Mao’s soldiers discovered her and killed her.

The martyrdom of little Li is shrouded with myth and mystery, but the Maoist takeover of China produced martyrs in Shanghai whose lives and deaths have been amply documented. One was Beda Chang (Xhang Boda in Pinyin), a Jesuit priest born in 1905. He received a doctorate in literature at the University of Paris in 1937, was ordained in 1940, and became dean of the faculty of arts at Shanghai’s Aurora University, a Jesuit institution founded in 1903.

In 1949 Mao Zedong completed his revolution in China. Shanghai Communist authorities called a meeting of local educators. Chang, who had advocated that Chinese Catholics try to make peace with the Communists, was asked to renounce his ties altogether with Rome. It was a prelude to Maoist China’s largely successful efforts to create a “patriotic” Chinese Catholic Church that its government controlled. In an eloquent speech Chang refused to cooperate with bringing the Chinese Church into schism.

On August 9, 1951, as he was playing mahjong with some fellow Jesuits in the faculty lounge at Aurora, police arrested Fr. Beda Chang. He was tortured, starved, deprived of sleep, and subjected to merciless, dawn-to-dusk interrogation sessions for three months. Finally, he fell into a coma and died on November 11, 1951.

His body was returned to the university the next day, and there was an outpouring of mourning and protest demonstrations by the Aurora students. Multiple Requiem Masses for him took place all over Shanghai which the government denounced as a “new type of bacteria warfare by the imperialists – a counterrevolutionary mental bacteria.” The police demanded that the demonstrations cease, and even guarded his grave to prevent veneration.

That did not stop Chinese Catholics from praying before Chang’s unmarked grave in droves, and reporting miracles. The government responded by effectively shutting down Aurora University by merging it with a public institution, launching decades of reprisals against Chinese Christians, Catholics and Protestants alike. Hundreds of Catholic priests, bishops, and lay people were imprisoned, tortured, and killed during the 1950s, and the Red Guards of the 1960s nearly obliterated all visible signs of Christianity in China with, among other things, the wholesale destruction of Catholic churches. Christianity has since experienced a revival.

But the age of Beda Chang and the making of martyrs is far from over. China’s current president, Xi Jinping, has pushed a kind of melding of Christian churches, including Catholic churches, with the Chinese Communist Party, requiring registration with authorities, arresting priests of China’s “underground” Catholic Church, closing church buildings, tearing down crosses, banning the teaching of religious doctrine, requiring priests to fashion their sermons around Xi’s apothegms, and even rewriting Bibles. A 2018 agreement with the Vatican that was supposed to have normalized relations with China by giving it a say in bishops’ appointments, has instead meant more arrests and torture of dissenting clerics, and the outright refusal of the Chinese government to approve bishops for at least half of China’s 98 Catholic dioceses (including the Diocese of Shanghai), leaving millions of lay Catholics leaderless. Although there is currently no formal movement to have Chang canonized, among Jesuits he is revered for his martyrdom—as among the Catholic residents of his native city from whom so much has been taken.

Fr. Jerzy Popieluszko: The Solidarity Martyr of Poland

Alphons (later Jerzy) Popieluszko was born in 1947 in the Polish People’s Republic, the Soviet puppet state that Josef Stalin had foisted upon Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill at the Yalta conference in 1945.

Propped up by the Red Army, which occupied all of Poland, the Communist Party quickly set up a police state. As a boy Alphons walked three miles daily to serve Mass at a church and then walked back to the church after school to pray the rosary. He was mocked by his teachers and fellow students for his faith. He resolved to become a priest and quietly boarded a train for a seminary in Warsaw right after his high-school graduation in 1965.

Just a year later, he was drafted into a special military unit for clerics that was designed to break their faith. Jerzy Popieluszko was regularly beaten and forced to stand for hours in freezing weather for such offenses as refusing to take off a religious medal that he wore around his neck. The beatings took such a toll on his heart and kidneys that his ordination was delayed until 1972.

In 1980 the workers at the Lenin Shipyards in Gdansk boldly formed their own union, Solidarity, the first independent labor union in the Soviet bloc. Father Popieluszko was assigned as chaplain for the striking Solidarity shipworkers. Huge numbers gathered for his monthly “Masses for the Fatherland,” in which he preached nonviolence and Christian charity. The Communist government stationed guards at his church to monitor his comings and goings.

In December 1982 a bomb was left at his door that he fortunately did not open. In December 1983 he was arrested and spent the next eight months in prison. On October 13, 1984, Father Popieluszko, frail but agile, mnaged through skilled and daring driving to avoid a staged, potentially fatal auto accident.

Then, on October 19, 1984, two national security service officers hijacked him in his car: They threw Father Popieluszko into the trunk of their own car and drove him into a forest. He nearly escaped when the car stopped, but the officers captured him and beat him so savagely that his face and hands became unrecognizable. They tied his hands and feet with a noose that extended around his neck, stuffed a cloth into his mouth and plaster into his nose, tied a bag of rocks around his feet. Then they dumped Father Popieluszko into a reservoir off the Vistula River.

His body was found ten days later. An autopsy revealed that he had probably been alive when he was thrown into the reservoir. More than 250,000 Poles attended his funeral. The officers who had killed him and their supervisor who had handed out the death order were later tried and found guilty of murder.

On June 6, 2010, Fr. Jerzy Popieluszko was officially beatified at an open-air Mass in Warsaw attended by more than 100,000 people.

Too many martyrs of Communism still languish in the deliberate obscurity that their totalitarian overlords have made part of their annihilation. Only recently has enough been known about some of those heroic Catholics who have died in near-anonymity to make them formal candidates for sainthood.

But telling the stories of the extraordinary faith and courage of those men and women we do know about matter.

In his 1997 book, The Rise of Christianity, sociologist Rodney Stark pointed out that many of the early Christian martyrs of the Roman Empire were celebrities even before their deaths, visited in prison and honored as heroes by their less courageous fellow Christians.

The totalitarians of the present day have pursued a tactic expressly designed to prevent the emergence of heroes and saints: mass shootings, news blackouts, incessant propaganda, the disappearing of victims behind forbidding masses of concrete, steel bars, and barbed wire, unmarked graves in remote locations: The sheer physical and technological power of the totalitarian state displayed front and center.

These stories matter. Remembering these heroes and future saints is an act of atonement. It is also a key victory over those tyrants who persecuted the Faith, who rebelled against all restrictions on their own political power, against those who rebelled first and foremost against God.

Martyrs of Communism, pray for us.

Charlotte Allen is executive editor of Catholic Arts Today. To learn more about Little Li, a eucharistic martyr, see Charlotte Allen’s previous Catholic Arts Today piece.